Washington,

DC, June 10, 2009 -

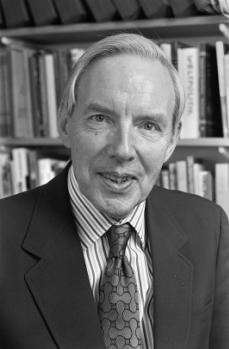

Last week the world lost

a luminary scholar of diplomatic and international history with the passing

of Ernest R. May, who served for 20 years on the National Security Archive's

advisory board.

In thinking about the immense and wide-ranging contributions

that Ernest made during the course of a career that lasted over fifty years,

a line from Wallace Stevens comes to mind:

“Description is revelation.” (from his poem

Description without Place).

Whether it be one of his many books, the innumerable scholarly

articles or the lectures given at Harvard, he always demonstrated a

fascination with and appreciation for the fine points of detail and the need

for multiple perspectives in describing and understanding key diplomatic

issues. His painstaking research into the complex pathways of the past marks

all his work, whether he was examining the origins of the Monroe Doctrine or

America’s entry into World War II, rethinking the causes for the fall of

France in 1940 (after personally walking the battlefields to get a better

sense of the landscape on which this crucial battle was fought), or

exploring the fascinating intricacies marking the different ways the U.S.

and the Soviet Union sought accuracy for their ICBMs, and how this affected

the arms race and the efforts to curb it.

The sheer range of his scholarly interests and contributions is

astonishing: 20th century great power diplomacy and military

history, early American foreign policy, the domestic roots of American

imperialism, the theory and practice of intelligence and how it should serve

policy-makers (seen most recently in his contribution to the 9-11

Commission’s report. His

fascinating memoir of working on the report is available here, courtesy of

The New Republic.), presidential decision-making, and last but

not least, his central role in organizing the “May Group” at the Kennedy

School of Government, which developed the analytical framework to guide

policy-makers in drawing upon the “lessons of history,” a framework

elaborated in the “Uses of History” classes and their later incarnations.

The insights developed by Ernest and his colleague, Richard

Neustadt, in this course were presented in their co-authored award-winning

book, Thinking in Time: The Uses of History for Decision-Makers. He

was also a key mover in initiating a major multi-national research project

on the history and role of nuclear weapons in post-war diplomacy, the

Nuclear History Project, which served as the launching pad for many

scholarly careers in the United States, England, France and Germany

(including the present author), not to mention providing the foundation for

the Archive’s collection of declassified documents on nuclear weapons.

The NHP can be viewed as a logical extension of the seminal

History of the Strategic Arms Competition that Ernest and two

colleagues, John Steinbruner and Thomas Wolfe, prepared for the Department

of Defense. (see the essay by William Burr below for more on this critical

study). All of these contributions and more are discussed in the Festschrift

presented to him a decade ago, Rethinking International Relations: Ernest

R. May and the Study of World Affairs, edited by Akira Iriye (Imprint

Publications, Chicago 1998).

Numerous obituaries have appeared which provide the basic facts

about Ernest’s career and accomplishments. We at the National Security

Archive want to

add our own personal note of appreciation for all that Ernest May has done

over the years to support the work of the Archive, as a member of its

Advisory Board and on the advisory panels for individual projects, and his

role in mentoring many of the scholars who have worked with the Archive.

Along with this expression of appreciation and loss, we would also like to

share some observations from other colleagues and former students of

Ernest’s, which you will find below.

I would like to add my personal recollections to these, as I was

privileged to be one of his graduate students in the 1980s. As might be

imagined, having Ernest May as an advisor was both an extraordinary

opportunity and a formidable challenge. It would be an understatement to say

he was an incredibly busy person. Though always maintaining an amazing pace,

combing teaching, research and consulting for the government, his office at

the Kennedy School (where he tended to spend most of his time rather than at

the History Department in Robinson Hall) was always open and welcoming.

After checking with Sally Makacynas, his loyal assistant and guardian of the

gates for nearly three decades, I tended to plan my visits with the care of

a minor military campaign, rehearsing in advance the questions I needed to

raise so I could move through my agenda with the maximum of efficiency.

Despite his hectic schedule, though, he never made me feel rushed and I

always left with questions answered but also usually a new batch of

questions or new avenues to pursue in my research.

Attending the Uses of History course was a unique

experience, as Ernest and Dick Neustadt engaged in the intellectual analog

to tag team wrestling, tossing the narrative line of the lecture back and

forth, while the students were scribbling furiously in the margins of their

case studies. The overarching theme – that history properly interrogated and

analyzed can provide useful information for those engaged in the task of

understanding and solving policy problems – left its mark on my subsequent

work, as on many others in academia and government.

His generous support was always available, be it in contacting

former officials I needed to interview or scholars whose work paralleled

mine. His assistance continued as I moved to the Archive, serving on the

advisory panel for my first project and lending his support to efforts to

establish a panel of scholars to advise the Defense Department on its

declassification programs. It was through his good offices that I had the

opportunity to meet such fascinating witnesses to history as Robert Bowie

and General A. J. Goodpaster, whose recollections of the Truman and

Eisenhower years (not least including General Goodpaster’s imitation of John

Foster Dulles) are a vital resource for all scholars studying the national

security policies of those administrations.

Equally memorable was his wry, at times self-deprecatory, sense

of humor. At one of the early NHP conferences, Ernest prefaced his remarks

by noting that though he had met a great many fascinating scholars at the

conference, he felt he should apologize in advance for not remembering their

names. The reason: as a historian he had to remember the names of hundreds

of dead people, and learning the name of someone new would necessitate

forgetting one of these, which professionally just was not an option.

As the recollections below underscore, Ernest as a person and a

scholar was always intensely curious and very generous. His dedication to

teaching is amazing (he was maintaining practically a full teaching load at

Harvard at the age of 80, a time when most people in any field are content

to rest on their laurels). While the subjects which drew his attention were

serious, often deadly so, there was no mistaking the enjoyment and sense of

play he exhibited when exploring them. His career and work are also marked

by his openness to the ways in which historical research and policy analysis

can be mutually enriching and open up new avenues for study. His dedication

to the highest standards of historical scholarship and emphasis on the need

for multi-archival research, combined with the span of his interests and the

depth of his knowledge, set a model for students and colleagues that was

both invigorating and somewhat daunting.

In attempting to sum up all the many interests and

accomplishments that mark Ernest’s life, another poet comes to mind, one who

like May began life out West but made New England his home. These lines

speak to the poet's desire for a life in which personal meaning and professional

accomplishment are not at odds:

But yield who will to their separation,

My object in living is to unite

My avocation and my vocation

As my two eyes make one in sight.

Only where love and need are one,

And the work is play for mortal stakes,

Is the deed ever really done

For Heaven and the future's sakes.

Robert Frost –

Two Tramps in Mud Time

In

his long career and strict adherence to the highest standards as a scholar

and a gentleman, Ernest May provides us with an object lesson in what can be

attained when one is able to achieve this unity of avocation and vocation.

He will be missed.

* * * *

* * *

Personal Reminiscences

from Former Graduate Students and Colleagues:

I still have my notes from Ernest May’s lectures for History

164a: American Foreign Relations to 1898. I took the course when I enrolled

as a first-year graduate student at Harvard in the fall of 1957. He was not

yet twenty-nine years old but was to be promoted to tenure two years later.

The first sentences of my notes of his first lecture, given on

September 23, 1957,

read: “Study of policy making. Broad range of political experience in

American diplomacy makes its history meaningful.” Here, it would seem, is a

nice summary of Ernest’s approach to the history of

U.S. foreign relations,

with its sharp focus on decision-making and on lessons of the past, which he

retained throughout his career. His lectures were the point of departure for

my (and many other scholars’) graduate and professional work. Some of us

have moved away from decision-making or from U.S. foreign affairs as key

scholarly concerns, but we always knew that Ernest was understanding of, and

open to, new approaches, which we were able to explore only because we were

confident that our mentor had provided us with a solid, common foundation.

Akira Iriye,

Harvard

University

* * * * *

Professionally, Ernest and his work always impressed upon me how

important it was to understand the domestic political contexts of foreign

policymakers. Decisions that, especially in retrospect, seem poor or even

bizarre can become comprehensible viewed this way.

Personally, Ernest was such a wonderful adviser because he

always seemed happy to see you. You would enter his office to a bright smile

and twinkling eye. You would leave confident in yourself because you knew he

believed in you.

Mike Barnhart, Professor

of History, SUNY-Stony Brook

* * * * *

Ernest May was a world famous scholar, a good friend with a wry

sense of humor, and a true gentleman. He had a marvelous capacity for

wonder, which inspired the questions he asked of history and of his

students, about whom he cared a great deal. His ability to answer the

questions that intrigued him, and to make those answers relevant to the

world in which he lived, made him a valuable expert for Congressional

hearings and Executive Branch commissions. He thus contributed to our

understanding of history, to interdisciplinary study and good governance.

Yet, Ernest also had a musician's sense of silence: the importance of pause

to melody. For those of us who were students of his, perhaps a tad

insecure, those silences taught us a lot, including not to rush to fill the

gap. This is a lesson - a gift - worth remembering.

Jennifer Sims, Visiting

Professor Security Studies Program, School of Foreign

Service

Georgetown

University

* * * * *

What strikes me as I reflect on my memories of Ernest May as my

graduate-program adviser in the 1980s is the quality of unassuming dignity

that he embodied. Here was one of the world's foremost historians of

diplomatic history, a distinguished scholar who also periodically did

important work for the top levels of government, and yet who displayed not a

hint of personal arrogance or pretension.

Instead, there was a charming shyness about his manner that

seemed to form an integral element of his gentlemanly self-possession and

that consistently left those who met him feeling intrigued. This was a

characteristic that Ernest May deployed to good effect as a pedagogical

tool: in the classroom and during office hours, he would raise questions and

delineate historical conundrums without spelling out what the answer was,

let alone imposing his opinion. By leaving his students wondering what he

really thought about an issue, Professor May was gently inducing them to

think for themselves. And that is all too rare a quality in a teacher. It is

sad to think that he is gone.

Aviel Roshwald,

Professor of History,

Georgetown

University

* * * * *

There will be many tributes to Ernest May over the next few

months. As a historian, an outstanding scholar of international relations,

a careful analyst of the arcane world of intelligence, Ernest May was a man

of many talents, not least his ability to read several languages and his

extraordinarily wide-ranging interests. (When computers were still in their

infancy, I remember him telling me that he had purchased a software program

that would allow him to train to be a pilot!) Of course there was always

tennis, which seemed to keep him perpetually youthful, vigorous, and always

engaging, with new ideas and projects. Despite all his achievements and

honors there was also a genuine humility to Ernest, rare among those who

taught at Harvard for more than half a century.

I knew Ernest for more than thirty years, ever since I walked

into his office as a new graduate student intimidated by the world-famous

professor. That feeling didn’t last long. Ernest was, at heart, a teacher,

and his method, sometimes direct, sometimes by example, had a profound

effect. He taught me to question my assumptions, interrogate the evidence,

and always consider the alternative hypothesis. One of his favorite

quotations, one he used often in challenging the government leaders and the

CIA officials he taught in his classes at the Kennedy School, was from

Oliver Cromwell, when he wrote to the General Assembly of the Church of

Scotland, “I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible you

might be mistaken.” My own hope is that the questioning Ernest provoked,

the belief he held so deeply that better policy decisions and better

governance could come from it, will be the legacy he leaves us.

Thomas Schwartz,

Professor of History,

Vanderbilt

University

* * * * *

Harvard was an intimidating place for a student from the Austrian provinces in the first couple years of graduate study in the 1980s. Ernest May, forever smiling and gently prodding, helped me accommodate to the place in his inimitable ways. He was gentle but also cryptic. When defining my dissertation topic on the post-World War II quadripartite occupation of Austria, he encouraged me to do it all --- political, economic, social and cultural relations. I was taken aback by such a broad charge but now realize that he just had given me a challenge. In retrospect, he helped me define my lifelong scholarly interests as I have done a lot of work on political and economic relations but am still working on social (migration) and cultural (public diplomacy, Americanization).

His intellectual persona liked to play the sphinx in many ways. When I attended the conference at Princeton on John Foster Dulles’s 100th birthday in 1988, I asked him whether he would be there too. He answered that he only attended conferences that were so interesting that he would take a bus there. He did not take a bus to Princeton that spring (I’m not sure whether he ever took a bus to a conference – he came by plane to the ones I was involved in invited him too in New Orleans and Munich).

May’s astounding range and depth as a historian I experienced when I served as his head TA in his CORE CURRICULUM course on “The Nuclear Era” in 1988. This course reflected his profound interest on nuclear issues in the 1980s (when SDI, “nuclear winter” and “nuclear ethics” were high on the agenda of U.S. foreign policy and international history). The only time I was admitted into his inner sanctum – his expansive study on top of Widener Library – was when I helped him collect the documents for a reader of case studies for that course. What astounded me most about his impeccably delivered lectures in that course, spoken freely with few notes, was that the first third of the lectures covered great thinkers of international relations, war and peace, from Machiavelli to Kant. Machiavelli, yes, but I did not anticipate May dwelling at length on Kant’s moral philosophy Zum Ewigen Frieden.

When I tried to see him last October in his Kennedy School office (without making prior arrangements) he was out of town. Sally, his gatekeeper, was out of town too – usually she would have relayed the latest news on him. May was always interested in my work (a rare trait for a Harvard Professor), Sally in my family. Now I regret even more to have missed him last fall. I will miss him but will continue to work on the life long challenge he set me up with – he will not be forgotten.

Günter Bischof, Marshall Plan Professor of History, University of New Orleans

* * * * *

Ernest R. May, John D. Steinbruner, and Thomas W. Wolfe, History of the Strategic Arms Competition, 1945-1972, Alfred D. Goldberg, editor, Office of the Secretary of Defense Historical Office, March 1981, Top Secret, excised copy, Chapters 1 through 5, with end-notes - Excerpts (Complete excised version available on DNSA). Compiled with Commentary by William Burr.

Ernest May was well known for his

long-standing relationship as a historical consultant for the Central

Intelligence Agency, but an extraordinary study, a History of the

Strategic Arms Competition, 1945-1972, that he helped produced for the

Office of Secretary of Defense may have been one of his more significant

historical projects for the U.S. government. In March 1981, the OSD

Historical Office published (internally) the top-secret History that

May prepared with two other scholars, John Steinbruner (then with Yale) and

Thomas Wolfe (RAND Corporation). Commissioned by Secretary of Defense James

Schlesinger in 1974, and supported by his successors, Donald Rumsfeld and

Harold Brown, the thousand-page plus study was completed in March 1981.

Believing that insufficient knowledge of

the recent past handicapped “critically important discussion” of nuclear

policy issues, Schlesinger wanted such a history to contribute to better

public understanding of the Cold War arms race (although he may have assumed

that the study would tend to validate U.S. government policy). Toward that

end, according to then-OSD Historian Alfred Goldberg, the authors believed

that an “exacting analysis of the historical past can yield evidence of

long-term trends and recurrent and repetitive cycles of behavior which

assist our understanding of the present and our planning for the future.”

A major objective was to reach a better

understanding of the U.S.-Soviet “interaction process” in order to

illuminate “hypotheses and models of the competition”; therefore, May and

his colleagues emphasized the need to “focus on the perceptions,

assessments, and reactions on both sides” [xii]. In particular, they tried

to determine the extent to whether it was possible to identify consistent

patterns of behavior in U.S. and Soviet decisions on nuclear forces and

force levels and the extent to which Moscow and Washington were imitating

each other, acting defensively, or acting “enterprisingly” for any variety

of reasons.

To produce their study, the authors had

extensive access to highly-classified sources in U.S. military and civilian

agencies, including the CIA. Given the huge complexity of their task and

the massive size of the relevant government record, they tried to get better

control of the primary sources by commissioning numerous supporting studies,

chronologies, and oral history interviews with former government officials.

For example, the Institute for Defense Analyses prepared top secret

histories of U.S. and Soviet command and control systems from 1945 to 1972,

while officials at the OSD Historical Office developed a massive

chronology. For Moscow’s role in the story, full sourcing was necessarily

impossible so the authors had to rely in part on what intelligence reporting

and analysis suggested about Soviet intentions and capabilities.

While Defense officials expected to produce

and publish an unclassified version of the History it never

materialized. Because it included so much then-highly classified

intelligence information, the Pentagon may have abandoned that part of the

project because it was too difficult. In any event, the May-Steinbruner-Wolfe

history has yet to be declassified in full. The Pentagon FOIA office

released a heavily excised version under appeal in 1990 and subsequent

attempts to challenge the excisions have been only partly successful.

Significantly more of the text was declassified in 2002, although excised

portions remain under appeal at the Pentagon.

The following excerpt from the History

of the Strategic Arms Competition include the first five chapters,

covering U.S. and Soviet military policy developments from the early Cold

War through the U.S. military build-up during 1950-53. On the U.S. side,

the authors produced a fine-grained analysis of armed services policies and

politics and inter-service rivalries, as well as organizational developments

on the civilian side, produced an illuminating and informative account of

the early development of U.S. nuclear policy and programs. On the Soviet

side, with less evidence May and his colleagues tried to tease out what they

thought shaped Stalin’s military policies.

To some extent reflecting orthodox views of

Cold War origins, the authors treated U.S. policy as a valid and inevitable

response to Soviet expansionism, without giving much weight to security

considerations driving Stalin’s policy. Nevertheless, their analysis of

Soviet capabilities recognized the significant degree to which Washington

had exaggerated views of, and reactions to, Soviet power, discounting the

“enormous damage” caused by the German invasion of the Soviet Union; thus,

“much that was written and said about the Soviet threat was a function less

of evidence about what the Soviets were actually doing than of fear of what

they might do” [81-82]. Nor did they see the U.S. as simply reacting to

Soviet initiatives: for example, they acknowledged that the U.S. military

buildup was not “wholly defensive” but also aimed at achieving a “suitable

world order”: “substantial increase in defense spending would ensure that

the Soviets and everyone else became fully aware of the omnipotence of the

United States” [120].