WEEK 1: THE SOVIET PLAN TO DESTROY GUANTANAMO (Posted June 4, 2008)

WEEK 3: TRACING THE NUCLEAR WARHEADS (Posted June 18, 2008)

WEEK 4: THE SHOOTDOWN OF MAJOR ANDERSON (Posted June 25, 2008)

WEEK 5: THE "EYEBALL TO EYEBALL" MYTH (Posted July 2, 2008)

ABOUT THIS SERIES

When Washington Post reporter Michael Dobbs first decided to write a book about the Cuban missile crisis, the question he was most frequently asked was, “What is there new to say about a subject that has been so exhaustively studied?” The answer, it turned out, was “a great deal.” Two years of research in half a dozen countries, including the United States, Russia, and Cuba, turned up a surprising amount of new information about the thirteen days in October 1962 when the world had its closest brush with nuclear destruction. His minute-by-minute narrative also explodes some long-accepted myths, repeated for decades by missile crisis scholars.

Over the next five weeks, the National Security Archive will publish some of the key primary sources behind One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War. The new information includes such episodes as a startling Soviet plan to destroy the Guantanamo naval base, the storage and handling of Soviet nuclear weapons on Cuba, and the “Eyeball to Eyeball” confrontation between U.S. and Soviet ships that never happened.

The revelations in One Minute to Midnight shed new light on presidential decision-making at moments of supreme tension. Some of the information that flowed into the Oval Office during the crisis was erroneous. U.S. intelligence analysts seriously under-estimated the number of Soviet military personnel in Cuba and failed to identify the bunkers for Soviet nuclear warheads, despite possessing photographic evidence that is being published for the first time in One Minute to Midnight. Soviet and U.S. leaders consistently misinterpreted each other’s signals.

American scholars have traditionally treated the Cuban missile crisis as a case study in the art of crisis management. The historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. praised Kennedy’s “brilliantly controlled…matchlessly calibrated” handling of the Soviets. The new revelations suggest that the crisis is better understood as an example of the limits of crisis management and presidential power. As told by Dobbs, the missile crisis is a case study of “government by exhaustion” in which frazzled policy-makers struggle to master the chaotic forces of history that they themselves helped to unleash. |

The Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962

The 40th Anniversary

Docments, photos, audio clips and more from the historic 40th anniversary conference in Havana

|

THIS WEEK: MISSING OVER THE SOVIET UNION

Washington, DC, June 11, 2008 - An American spy plane went missing over the Soviet Union at the height of the Cuban missile crisis for one and a quarter hours without the Air Force informing either President Kennedy or Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, according to a new book by Washington Post reporter Michael Dobbs (drawing on documents posted here today by the National Security Archive.)

|

U.S. Air Force Captain Charles Maultsby. |

The accidental intrusion into Soviet air space by a U-2 belonging to the Strategic Air Command on October 27, 1962, is still classified top secret by the Air Force and has received little attention from missile crisis historians. Dobbs discovered a map in the National Archives that reveals for the first time the precise route taken by Captain Charles Maultsby as he was chased by Soviet Mig Fighters over the Chukotka Peninsula.

This is the second of five postings looking at the new material in One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy,Khrushchev, and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War, which draws on the National Security Archive's long-standing documentary work on the Cuban Missile Crisis. The Air Force was able to track Maultsby's flight route by intercepting Soviet Air Defense communications, but did not inform McNamara about the incident until Maultsby left Soviet air space, ran out of fuel, and glided home to Alaska. Khrushchev later expressed concern that the intruding U.S. plane could have been mistaken "for a nuclear bomber, which might push us to a fateful step."

Both the Soviet Union and the United States were conducting nuclear tests in the atmosphere in October 1962. In order to monitor the Soviet tests at Novaya Zemlya, the United States sent U-2 planes to the North Pole to collect high altitude radioactive air samples. The atmospheric nuclear tests and the air sampling missions continued throughout October 1962 even as the two superpowers prepared to go to war over Cuba.

|

Captain Maultsby's U-2 plane, serial number 56-715 |

Neither the White House nor the highest levels of the Pentagon were paying any attention when Captain Charles F. Maultsby took off from Eilson Air Force Base in Alaska at 4 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time (midnight Alaska) on October 27, 1962. His return mission to the North Pole was scheduled to last eight hours. A Duck Butt air rescue plane accompanied him as far as Barter Island off the northern coast of Alaska.

Half way to the North Pole, Maultsby was blinded by the aurora borealis, or northern lights and had trouble taking fixes with the stars. At the time that he should have been landing back at Eilson AFB-- noon EDT--he penetrated the borders of the Soviet Union. According to a chart found by Dobbs at the John F. Kennedy library, Mig fighters were scrambled from Pewek air base off the northern coast of Chukotka at 1556 GMT--1156 EDT--in an attempt to intercept Maultsby. They accompanied him as he flew south over Soviet territory, but were unable to shoot the U-2 down.

Click on the icons for further details on Maultsby's flight (View Larger Map)

MiG fighters were also scrambled from Anadyr on the southern coast of Chukotka, and made an attempted intercept at 1629 GMT (1229 EDT). A chart found by Dobbs in the records of the State Department Executive Secretariat at the National Archives shows the MiGs tracking Maultsby as he turned eastwards back toward Alaska. A more detailed image of this map can be seen here. MiG fighters were also scrambled from Anadyr on the southern coast of Chukotka, and made an attempted intercept at 1629 GMT (1229 EDT). A chart found by Dobbs in the records of the State Department Executive Secretariat at the National Archives shows the MiGs tracking Maultsby as he turned eastwards back toward Alaska. A more detailed image of this map can be seen here.

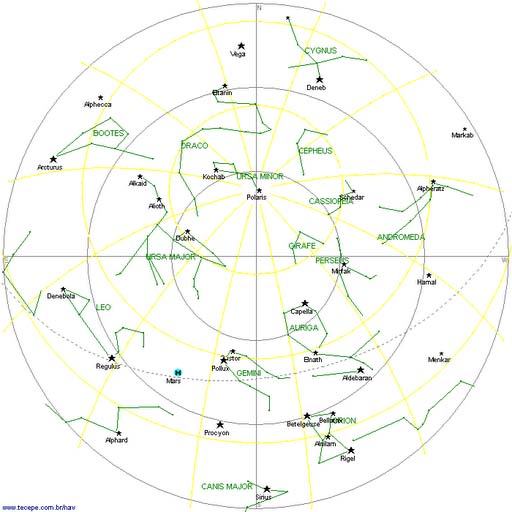

Former SAC pilots and SAC headquarters staff told Dobbs that the U.S. was able to track both Maultsby, and the Soviet Migs attempting to shoot him down, by intercepting Soviet air defense traffic. But they were unable to share this information with the pilot, as the U.S. eavesdropping capabilities were a closely guarded national secret. Navigators guided Maultsby out of Soviet air space by ordering him to turn left until he could see Orion's Belt off his right wingtip. With the constellation observable to his south, Maultsby would be flying westwards, back home toward Alaska. Here is a chart of the nighttime sky as Maultsby observed it.

The Alaska Air Defense Command scrambled a pair of F-102 interceptors armed with nuclear warheads from Galena AFB to guide Maultsby home and intercept the Soviet Migs. Maultsby ran out of fuel as he exited Soviet air space, gliding for nearly an hour before landing at an airstrip at Kotzebue on the western tip of Alaska.

With events in Cuba consuming everybody's attention, neither the Pentagon nor the White House had considered the possibility that a U-2 might go missing over the Soviet Union on the most dangerous day of the crisis. Maultsby's own commander, Colonel John A. Des Portes, was unaware that he had been dispatched to the North Pole until he received an urgent telephone call from SAC headquarters, demanding to know "what in the hell I was doing with a plane over Russia." Des Portes had his hands full with the simultaneous shootdown of a U-2 over Cuba.

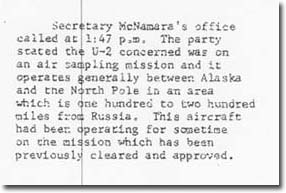

Pentagon and White House records show that defense secretary Robert McNamara was not informed that the U-2 was missing over the Soviet Union until 1.41 p.m. EDT, more than an hour and a half after Maultsby entered Soviet air space. McNamara rushed out of a meeting with the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the Tank and informed the president by telephone four minutes later, at 1.45 p.m. The Pentagon informed the State Department at 1.47 p.m, according to a contemporaneous State Department memo. Pentagon and White House records show that defense secretary Robert McNamara was not informed that the U-2 was missing over the Soviet Union until 1.41 p.m. EDT, more than an hour and a half after Maultsby entered Soviet air space. McNamara rushed out of a meeting with the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the Tank and informed the president by telephone four minutes later, at 1.45 p.m. The Pentagon informed the State Department at 1.47 p.m, according to a contemporaneous State Department memo.

According to a 1975 oral history interview with Air Force General David Burchinal, McNamara rushed out of the Pentagon meeting yelling hysterically "this means war with the Soviet Union. The president must get on hotline to Moscow!" Burchinal probably embroidered this acount ssomewhat as the Washington-Moscow hotline was only installed after the missile crisis.

At 2 p.m., the Pentagon provided further details to the White House. "Apparently gyro trouble developed, and he got off course. Picked up by HFDF (high frequency direction finder) off Wrangel island. Seems to have overflown, or come close to, Soviet territory. Not clear at this time exactly what cause was. Russian fighters scrambled—ours too. Now gliding into Kotzebue, Alaska."

Maultsby landed at Kotzebue at 2.25 p.m. EDT after a flight of 10 hours, 25 minutes, the longest ever recorded for a U-2, as reported in this SAC memorandum. McNamara promptly ordered the recall of a second U-2 plane that had followed him on yet another air sampling mission to the North Pole, according to a Pentagon memo. He also ordered the cancellation of all U-2 air sampling missions and a full Air Force investigation into the causes of the accident.

In a message to Kennedy on October 28 agreeing to dismantle his missile sites on Cuba, Khrushchev expressed concern that the American intruder could have "easily" been mistaken "for a nuclear bomber, which might push us to a fateful step." The Kennedy administration ordered the temporary grounding of all U-2 missions, but hushed up the incident as best it could.

Forty-six years later, the results of the Air Force investigation have still not been published. The official Air Force history of Maultsby's unit describes his flight as "100 per cent successful."

For more information on SAC U-2 flights during the crisis, as well as on SAC nuclear weapons activities, see the recently declassified history of Strategic Air Command Operations During the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962.

If you have Google Earth installed on your computer, you can follow Maultsby's overflight of the Soviet Union through precise coordinates and photographs by downloading this Google Earth layer and opening it in the free Google Earth application.

Open 'Maultsby_U2_overflight' layer in Google Earth Open 'Maultsby_U2_overflight' layer in Google Earth

If you do not currently have Google Earth installed on your computer, you can access this information by taking the following steps:

1. Download and install the free Google Earth application.

2. Download the Google Earth layer on the Maultsby U-2 overflight and open the file using the Google Earth application.

More information on Maultsby's overflight of the Soviet Union, including the pilot's personal account of his ordeal, is available in One Minute to Midnight, available through Amazon.com.

MORE POSTINGS

WEEK 1: THE SOVIET PLAN TO DESTROY GUANTANAMO (Posted June 4, 2008)

WEEK 3: TRACING THE NUCLEAR WARHEADS (Posted June 18, 2008)

WEEK 4: THE SHOOTDOWN OF MAJOR ANDERSON (Posted June 25, 2008)

WEEK 5: THE "EYEBALL TO EYEBALL" MYTH (Posted July 2, 2008)

|