home | about | documents | news | publications | FOIA | research | employment | search | donate | mailing list

RELATED ARTICLE

How to Fight a Nuclear War

William Burr, Foreign Policy Magazine, September 14, 2012

Special Collection: Key Documents on Nuclear Weapons Policy, 1945-1990

Jimmy Carter's Controversial Nuclear Targeting Directive PD-59 Declassified

Designed to Give President More Choices in Nuclear Conflict than "All-Out Spasm War"

White House Officials Envisioned Prolonged Nuclear Conflict Where High-Tech Intelligence Systems Provided a "Look-Shoot-Look" Capability

Leak of PD-59 Exposed White House Exclusion of State Department in National Security Decisions

National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 390

Posted - September 14, 2012

For more information contact:

William Burr - 202/994-7000 or nsarchiv@gwu.edu

Washington, D.C., September 14, 2012 – The National Security Archive is today posting - for the first time in its essentially complete form - one of the most controversial nuclear policy directives of the Cold War. Presidential Directive 59 (PD-59), "Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy," signed by President Jimmy Carter on 25 July 1980, aimed at giving U.S. Presidents more flexibility in planning for and executing a nuclear war, but leaks of its Top Secret contents, within weeks of its approval, gave rise to front-page stories in the New York Times and the Washington Post that stoked wide-spread fears about its implications for unchecked nuclear conflict.

The National Security Archive obtained the virtually unexpurgated document in response to a mandatory declassification review request to the Jimmy Carter Library [See Document 12]. Highly classified for years, PD 59 was signed during a period of heightened Cold War tensions owing to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, greater instability in the Middle East, and earlier strains over China policy, human rights, the Horn of Africa, and Euromissiles.

In this context, the press coverage quickly generated controversy by raising apprehensions that alleged changes in U.S. strategy might lower the threshold of a decision by either side to go nuclear, which could inject dangerous uncertainty into the already fragile strategic balance. The press coverage elicited debate inside and outside the government, with some arguing that the PD would aggravate Cold War tensions by increasing Soviet fears about vulnerability and raising pressures for launch-on-warning in a crisis. Adding to the confusion was the fact that astonishingly, even senior government officials who had concerns about the directive did not have access to it.

With other recently declassified material related to PD-59, today's publication helps settle the mystery of what Jimmy Carter actually signed, [1] as well as shedding light on the origins of PD-59 and some of its consequences. Among the disclosures are a variety of fascinating insights about the thinking of key U.S. officials about the state of nuclear planning and the possible progression of events should war break out:

- PD-59 sought a nuclear force posture that ensured a "high high degree of flexibility, enduring survivability, and adequate performance in the face of enemy actions." If deterrence failed, the United States "must be capable of fighting successfully so that the adversary would not achieve his war aims and would suffer costs that are unacceptable." To make that feasible, PD-59 called for pre-planned nuclear strike options and capabilities for rapid development of target plans against such key target categories as "military and control targets," including nuclear forces, command-and-control, stationary and mobile military forces, and industrial facilities that supported the military. Moreover, the directive stipulated strengthened command-control-communications and intelligence (C3I) systems.

- President Carter's first instructions on the U.S. nuclear force posture, in PD-18, "U.S. National Strategy," supported "essential equivalence", which rejected a "strategic force posture inferior to the Soviet Union" or a "disarming first strike" capability, and also sought a capability to execute "limited strategic employment options."

- A key element of PD-59 was to use high-tech intelligence to find nuclear weapons targets in battlefield situations, strike the targets, and then assess the damage-a "look-shoot-look" capability. A memorandum from NSC military aide William Odom depicted Secretary of Defense Harold Brown doing exactly that in a recent military exercise where he was "chasing [enemy] general purpose forces in East Europe and Korea with strategic weapons."

- The architects of PD-59 envisioned the possibility of protracted nuclear war that avoided escalation to all-out conflict. According to Odom's memorandum, "rapid escalation" was not likely because national leaders would realize how "vulnerable we are and how scarce our nuclear weapons are." They would not want to "waste" them on non-military targets and "days and weeks will pass as we try to locate worthy targets."

- An element of PD-59 that never leaked to the press was a pre-planned option for launch-on-warning. It was included in spite of objections from NSC staffers, who saw it as "operationally a very dangerous thing."

- Secretary of State Edmund Muskie was uninformed about PD-59 until he read it about in the newspapers, according to a White House chronology. The State Department had been involved in early discussions of nuclear targeting policy, but National Security Adviser Brzezinski eventually cut out the Department on the grounds that targeting is "so closely related to military contingency planning, an activity that justly remains a close-hold prerogative and responsibility" of the Pentagon.

- The drafters of PD 59 accepted controversial ideas that the Soviets had a concept of victory in nuclear war and already had limited nuclear options. Marshall Shulman, the Secretary of State's top adviser on Soviet affairs, had not seen PD-59 but questioned these ideas in a memorandum to Secretary Muskie: "We may be placing more weight on the Soviet [military] literature than is warranted." If the Soviets perused U.S. military writing, it could "easily convince them that we have such options and such beliefs." Post-Cold War studies suggest that Shulman was correct because the Soviet leadership realized that neither side could win a nuclear war and had little confidence in the Soviet Union's ability to survive a nuclear conflict.

Background

When Jimmy Carter became president in January 1977, he inherited nuclear weapons targeting policies from his Republican predecessors, who had sought ways to give U.S. presidents alternatives to the terrifyingly massive and rigid pre-planned options of the Single Integrated Operational Plan [SIOP]. To make nuclear threats more plausible and to give presidents more choices than the SIOP attack options, in January 1974, Richard Nixon signed National Security Decision Memorandum [NSDM] 242. A few months later, in April 1974, Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger signed Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy [NUWEP] which provided guidance for the creation of limited, selective, and regional attacks, with more detail for major attack options. Among the goals set for Major Attack Options in the NUWEP was the destruction of "selected economic and military resources of the enemy critical to post-war recovery," including political and military leadership targets. With respect to economic recovery targets, the NUWEP called for inflicting "moderate damage on facilities comprising approximately 70% of [the Soviet or Chinese] war-supporting economic base."

The perception that the NSDM-242 exercise had not given the President more options for crisis-confrontation situations [see Document 1 below] led the Carter White House to initiate a nuclear targeting review that eventually produced PD-59. The Joint Strategic Target Planning Staff [JSTPS] had shown proficiency in creating massively destructive "pre-planned" nuclear strikes against Soviet military targets, but the Carter White House saw them as largely irrelevant. As Bzezinski explained, the "very likelihood of all out nuclear war is increased if all out spasm war is the only kind of nuclear war we can fight." Starting with the premise that conflict was more likely to start in Central Europe or Northeast Asia, the architects of PD-59 believed that high-tech reconnaissance systems could give the president and his advisers a "look-shoot-look" capability to improvise targeting during war. In this way, they could strike Warsaw Pact forces on the move with nuclear weapons instead of launching SIOP attacks against major military targets in the Soviet Union.

The JSTPS had responsibility for the SIOP, under the direction of an Air Force general who wore a second hat as Commander-in-Chief of the Strategic Air Command. In this capacity, he had a powerful influence in the military bureaucracy. Brzezinski aide William Odom saw little value to the massive SIOP attack options, believing that a flexible targeting system could help provide an adequate deterrent, but he could not wish SAC and the SIOP out existence because its leaders believed that those options were critical to the national defense. Thus, PD 59 was necessarily a bureaucratic compromise by providing for pre-planned attack options, including launch-on-warning but also flexibility to prepare war plans on "short notice" and strategic reserve forces for later stages of a conflict. War plans could range from massive attacks to "flexible sub-options" against broad classes of targets. To ensure that attack plans could be improvised, PD-59 mandated the creation of "staff capabilities" in the military and at the Pentagon that could "develop operational plans on short notice … based on the latest intelligence."

War plans developed under PD-59 were to "put the major weight of the initial response on military and control targets." Target systems would include tactical and strategic nuclear forces, military command centers, conventional military forces including armies in motion, and industrial facilities supporting military operations. Dropping "critical" recovery targets as a priority, pre-planned options would include "attacks on the political control system and on general industrial capability" either promptly or as "relatively prolonged withholds" that could be attacked later in a conflict. Yet the initial press coverage of PD-59 was slightly misleading by suggesting that targeting before the directive had focused on urban centers; the SIOP had always given priority to military targets and had provisions for excluding attacks on urban-industrial complexes unless Moscow had already attacked U.S. cities.

That the White House had initiated a major review of nuclear targeting remained largely secret until President Carter signed PD-59. [2] Nevertheless, the administration's interest in acquiring capabilities, such as the MX ICBM, for counterforce strikes against Soviet strategic targets had been in the news before the existence of the PD leaked. [3] In early August 1980 headline in national newspapers brought out the larger secret: the existence a new directive changing nuclear war planning, with the first story appearing in the Boston Globe on 3 August 1980. The news stories correctly emphasized key elements of PD-59, that it sought capabilities for "prolonged but limited nuclear war," and that it gave priority to military and leadership targets, and a capability to "find new targets and destroy them" once a war began. [4]

The press coverage cited "shudders" among former government officials such as Herbert Scoville who worried that the search for "less fearsome options for using nuclear weapons would reduce the inhibitions for employing them." Moreover, Federation of American Scientists Director Jeremy Stone asked "Who would be there to turn off the war if we nuked Soviet command centers?" Stone warned about pressures for "firing on warning", although the language on launch-on-warning was one element of the PD that stayed secret. [5] Those concerns dovetailed with private misgivings among State Department officials, such as Marshall Shulman who worried that the reported emphasis on the role of leadership and C3I targets could "only increase Soviet perceptions of vulnerability" and introduce "further instability in the strategic balance."

Newspaper stories about PD-59 raised questions whether President Carter and his advisers had adequately consulted Secretary of State Muskie and the State Department before or after signing the PD. Muskie first learned about the PD from the press coverage, which then noted his "unhappiness that he knew so little about the new doctrine." This became an issue at the State Department, which did not have a copy of the directive and where senior officials argued that the Department should be involved in the "formulation and assessment of national security decisions that have significant foreign policy implications." Muskie's top advisers recommended that he seek an understanding with President Carter that this should not have happened and should not happen again, but whether the two reached a meeting of the minds on this point is not clear.

One of the purposes of the PD was to influence more detailed guidance on nuclear targeting. Top-level officials at the Pentagon and the Joint Strategic Target Planning Staff would use the ideas codified in the directive to develop more detailed instructions for shaping the production of pre-planned options and for developing "look-shoot-look" capabilities. By October 1980, Secretary of Defense Brown had approved the latest Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy to provide guidance for targeting in a crisis [see Document 21] Yet the ink had hardly dried on Brown's NUWEP when Ronald Reagan defeated Jimmy Carter for the presidency; in October 1981 the new administration supplanted PD-59 with National Security Decision Directive 13, "Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy." NSDD-13 influenced NUWEP-82 which replaced Brown's guidance.

NSDD-13 was eventually declassified; years before that happened, Odom wrote that it "carr[ied] the general thrust of PD-59, but with less comprehension of what was needed," and that "little or nothing of consequence was done to pursue this doctrinal change." [6] Future declassifications may test the accuracy of Odom's judgments. In any event, PD-59 (as well as NSDM-242) set the mold for target planning during the decades that followed, during and after the Cold War era. According to a recent Government Accountability Office report, "the process for developing nuclear targeting and employment guidance … has remained virtually unchanged since 1991." Presidential directives and secretary of defense guidance approved during the George W. Bush administration included familiar themes. They provided for a planning structure "designed to avoid an 'all-or-nothing' response to a nuclear attack," identified "potential adversaries" and "scenarios" requiring pre-planned options, and emphasized a "capability to rapidly develop new options." While President Obama has set a nuclear-free world as a policy goal, it is unlikely that nuclear planning arrangements will change significantly in the foreseeable future.

READ THE DOCUMENTS

Document 1: Memorandum from national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski to President Carter, "Our Nuclear War Doctrine: Limited Options and Regional Nuclear War Options," 31 March 1977, Top Secret

Source: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum [JCL], National Security Adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski Material, Subject File, box 47, file 8 [Copy from Remote Access Capture database]

In the weeks after Jimmy Carter became president, national security adviser Brzezinski became acquainted with the state of U.S. nuclear war planning. As this memorandum makes clear, both he and President Carter were dissatisfied with what they had heard from briefings on the SIOP and NSDM 242. While the Nixon administration had established a planning process that was supposed to create more attack options for a president, most of the options that target planners had created were "massive in both direct and collateral damage." Brzezinski saw little progress in creating Limited Nuclear Options [LNOs] or in producing policy guidance for them. Moreover, he saw significant operational problems, such as where and how presidents could conduct a "limited nuclear war" and the vulnerability of the President and advisers to a nuclear strike. For these problems and related ones, Brzezinski and Carter wanted the Pentagon to produce explanations and solutions.

Documents 2A and B

A. Walter Slocombe, Acting Assistant Secretary of Defense, to Director of Defense Research and Engineering et al., "U.S. National Strategy (Presidential Directive/NSC-18) (PD/NSC-18)," 30 August 1977, Top Secret

B. Walter Slocombe, Acting Assistant Secretary of Defense, to Director of Defense Research and Engineering et al., "Follow-On Studies for PD/NSC-18," 1 September 1977, Top Secret

Source: Defense Department mandatory declassification review [MDR] releases

To start getting answers from the Pentagon on targeting policy but also to give guidance for nuclear strategy in general, Jimmy Carter's national security staff issued Presidential Directive-18. Codifying a middle-of-the-road "competitive co-existence" strategy toward relations with the former Soviet Union, [7] the PD emphasized the U.S.'s "critical advantages" (economic, technological, and political). While embracing efforts to "counterbalance" Soviet influence in "key areas," the administration sought cooperation to avoid crises and confrontation as well as arms control agreements that increased "stability" and reduced strategic competition. To support those purposes, PD-18 included "initial guidance" on military strategy, including strategic force objectives and programs. Thus, rather than seeking outright strategic superiority, which could have led to a no-win arms competition, Carter sought a posture of "essential equivalence," abjuring a "first strike capability" and emphasizing the importance of "strategic stability." Nevertheless, to offset Soviet strategic advantages, maintaining "essential equivalence" would mean retaining (or developing) those strategic advantages that United States already enjoyed.

PD-18 promised "separate instructions" to the secretary of defense on targeting policies and a directive for "follow-on studies" soon reached the Pentagon. Besides asking for a study of current targeting policy and recommended criteria, Brzezinski requested analysis of several options, including a strike which targeted 70 percent of all Soviet economic, political, and military "recovery resources" and 90 percent of "all other identified Soviet military targets and related command, control, and communications facilities." Moreover, he sought an analysis of capabilities for "hard-target kill," war-time capabilities to locate and strike targets using reserve forces, and the future of the Triad, among other topics. The source of this document is the retired files of the late Arms Control and Disarmament Agency; the marginal notes were written by a highly skeptical ACDA official.

Document 3: Nuclear Targeting Policy Review, Phase I1 Report, Executive Summary, November 1978, Top Secret, Excised copy

Source: MDR release, under appeal at ISCAP

When Harold Brown followed up the PD-18 requests, he commissioned the Nuclear Targeting Policy Review (NTPR), a study led by former State Department official, Leon Sloss. The document reproduced here is a summary of the larger NTPR report. While key findings remain classified, a major conclusion on nuclear deterrence, survived unscathed (see pages i-ii). This conclusion flowed from a controversial conclusion: that the Soviets had a "concept of victory, even in nuclear war." That is, U.S. intelligence and Soviet experts alike agreed that the "Soviets seriously plan to face the problems of fighting and surviving a nuclear war should it occur, and of winning, in the sense of having military forces capable of dominating the post-war world."

Post-Cold War studies suggest that this was an exaggerated view and that the Soviet military leadership believed that neither side could win, had "no working definition of victory," and had "little real confidence in the USSR's ability to survive a nuclear war." [8] Nevertheless, those assumptions led the architects of targeting policy to conclude that to disabuse Moscow of any idea that victory was possible, U.S. plans and capabilities should "minimize Soviet hopes of military success" by targeting military forces, command and control, and "military support" installations.

Documents 4A and B:

A. Detailed Minutes, Special Coordination Committee Meeting, "Strategic Forces Employment Policy," 4 April 1979, Top Secret

B. Vic Utgoff, NSC Staff, to Zbigniew Brzezinski, "SCC on Strategic Forces Employment Policy," 5 April 1979, enclosing "Summary of Conclusions," for Special Coordination Committee Meeting,, "Strategic Forces Employment Policy," 4 April 1979, Top Secret

Source: JCL, National Security Adviser, Subject File, box 35, P[residential] D]irective] 59 [8/78-4/79]

A meeting of the Special Coordination Committee on strategic targeting policy led off with a report by Secretary of Defense Brown who, with Brzezinski, played a key role in the creation of PD 59. Referring to a report, probably the full version of document 3, Brown argued that it was "not urging a big change in targeting policy" because it emphasized traditional target categories: Soviet military targets, command-and-control (leadership targets), and urban-industrial targets. Yet, one of his concepts, the idea of targeting Soviet conventional forces "on the move", during war, was relatively new.

While Brown emphasized the need for adequate plans for an all-out "spasm" war based on the SIOP, Brzezinski wanted more limited options to all-out nuclear war, arguing that the "very likelihood of all out nuclear war is increased if all out spasm war is the only kind of nuclear war we can fight." The late Spurgeon Keeny, then-Arms Control and Disarmament Agency deputy director, argued that the study proposed shifting the emphasis of targeting from urban-industrial to military targets, but this was a disputed point, with Brown insisting that the shift was small. The drafter of the transcript also took exception to Keeny's argument.

Later in the meeting the discussion turned to what "really" most deterred the Soviets leadership, with Brzezinski and Secretary of State Vance agreeing that it was "the threat to the Soviet population." Although directly targeting civilian populations was illegal under international law, all understood what targeting industry meant. Brown, however, disagreed with Vance and Brzezinski's interpretation of what deterred Moscow, probably because of his predisposition to emphasize military and leadership targets.

The summary of the SCC meeting includes additional information: a list of Defense Department follow-on studies, and issues for discussion at future meetings, including included proposals to remove China from the SIOP (e.g., by using non-SIOP forces), "economic targeting," "targeting to regionalize the Soviet Union," and hard-target kill capabilities. Those issues would be discussed in terms of the requirements of stable deterrence, crisis bargaining, and effective war management.

Document 5: Victor Utgoff, William Odom, and Fritz Ermarth to David Aaron and Zbigniew Brzezinski, "Targeting Study SCC," 24 April 1979, Top Secret

Source: JCL, National Security Adviser, Subject File, box 35, P[residential] D]irective] 59 [8/78-4/79]

The records of subsequent SCC meetings on the targeting policy review have not been declassified, but a briefing memorandum for Brzezinski is available on one of them. As Brzezinski's aides indicated, they wanted the meeting to educate top ACDA and State Department officials on some sensitive points, including vulnerabilities of the National Command Authority (NCA) to nuclear attack, their view that U.S. nuclear war plans were like World War I military plans in their rigidity, and the Soviet Union's allegedly greater ability to fight a nuclear war compared to the U.S.'s "spasm war" response.

Document 6: Memo on "building blocks" from Eugene Durbin, Office ofSecretary of Defense, to Mike [probably D. Michael Landi, RAND Corporation], 26October 1979, with cover note to Bill Odom, n.d. , unclassified

Source: JCL, National Security Adviser, General Odom File, box 35,Nuclear Targeting 7/79-1/81

Two related exercises unfolded during late 1979 and into 1980, although withdelays and interruptions owing to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, whichpreoccupied the national security bureaucracy. One was the drafting of a presidential directive. The other was the drafting of guidance for target planners--"Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy"--that would be informed by the PD. A key element in the NUWEP guidance was the idea of "building blocks," the concept of basing targeting plans on discrete or interrelated options. The idea apparently had its origins at the RAND Corporation and was further developed in the targeting review that Leon Sloss directed.

Durbin's memorandum raised issues for further discussion about the building blocks concept, such as whether they should be treated as "cuts of the target base" or as "executable options" themselves, constraints on the numbers of "executable options" (e.g., how many options could a "President be expected to understand"), and measures for evaluating building blocks, including efficiency costs, risks, collateral damage, and Soviet perceptions.

The author of this paper, Eugene Durbin, then working at the Office of Secretaryof Defense, had been head of the Logistics Department of the RAND Corporation.The paper mentions other RAND analysts, including William Jones, and "Andy,"probably Andrew Marshall, formerly of RAND, and the well-known head of the Pentagon's Office of Net Assessment since the 1970s.

Document 7: William Odom to Zbigniew Brzezinski, "Draft PD on Nuclear Targeting," 22 March 1980, Top Secret

Source: JCL, National Security Adviser, Subject File, box 35, P[residential] D[irective] 59 [3/80-4/80]

By the spring of 1980, Brzezinski's military assistant, William Odom, was working on a draft of what became PD-59. Harold Brown had sent a draft from the Pentagon, but Odom reworked it so that it reflected White House preferences and priorities. While SAC and the JSTPS had excelled at developing the SIOP, [9] new intelligence capabilities made it possible to identify new targets and coordinate nuclear strikes on them within minutes and hours. This made the SIOP an "obstacle to further progress." Even the limited nuclear options that had been prepared under NSDM 242 were problematic, partly because they might not meet the needs of an unforeseen crisis.

Odom wanted to use the PD to get rid of the SIOP altogether but he realized that the bureaucratic obstacles were powerful. Indeed, as he wrote in this memorandum, he believed that there had to be a section on "pre-planned options" so that he would not "shock the SIOP people and SAC." [10] Nevertheless, he sought to make the SIOP largely irrelevant by seeking "genuine flexibility" that would make it possible to follow a "look-shoot-look" approach just as Harold Brown had done during a recent military exercise where he was "chasing general purpose forces in East Europe and Korea with strategic weapons." Rather than developing pre-planned options which could never truly anticipate future contingencies, Odom wanted a "national military operational staff" which could develop options as needed The joint chiefs could not play that role but military exercises involving the president and the secretary of defense could help.

Reviewing the draft presidential directive (not declassified with this memorandum), Odom described the key passages including sections on flexibility, targeting priorities, and command-control-communications and intelligence (C3I). In the section on C3I, Odom explained how he thought nuclear war would play out. Tacitly rejecting Brown's view that nuclear war was not likely to stay limited, Odom described a prolonged nuclear war that avoided mass civilian casualties. "Rapid escalation" was not likely because national leaders would realize how "vulnerable we are and how scarce our nuclear weapons are." They would not want to "waste" them on non-military targets and "days and weeks will pass as we try to locate worthy targets." Odom saw periods of nuclear strikes with "panic and confusion" followed by a search for targets.

Document 8: William E. Odom and Jasper Welch to Brzezinski, "Targeting Policy," 26 March 1980, Top Secret

Source: JCL. National Security Adviser, Subject File, box 35, P[residential] D]irective] 59 [3/80-4/80]

To move the work on the PD forward, Odom and a colleague, Air Force General Jasper Welch, drafted a memorandum from Brzezinski to Brown, which forwarded the draft directive (not yet declassified). Brzezinski informed Brown that he did not want interagency coordination of the directive at the SCC level because "it is so closely related to military contingency planning, an activity that justly remains a close-hold prerogative and responsibility of the Department of Defense and the Joint Staff." This explains why, as it would turn out, bringing the secretary of state into the process, before Carter signed the directive, had no priority at all. Muskie's predecessor, Cyrus Vance, and Deputy Secretary of State Warren Christopher, had already registered dissents about the need for a directive; no doubt Brzezinski wanted no more debate. [See Document 15 below.]

Document 9: William E. Odom and Jasper Welch to Brzezinski, "Draft PD on Nuclear Employment Policy," 17 April 1980, Brown memo and comments on revisions attached, excised copy, Top Secret

Source: JCL, National Security Adviser, Subject File, box 35, P[residential] D]irective] 59 [3/80-4/80]

This memorandum illuminates the process that produced the final draft of PD-59. While Harold Brown had produced a draft that was very close to the White House version, Odom and Welch had disagreed with some of Brown's language and suggested revisions to meet basic Defense Department objectives. On some points, for example, a paragraph on the first page that they wanted to delete, on whether to refer to target "priorities" or "categories," Odom and Welch got their way. But on others, for example, whether to preserve references to Cuba, Vietnam, North Korea, and China, Brown prevailed, as he did on the language on launch-on-warning. Odom and Welch saw that as "operationally a very dangerous thing" and not properly belonging in the PD. [11] Characteristically, when Defense Department reviewers declassified Brown's draft they excised the target categories and information on other points, such as launch-on-warning.

Document 10: Department of State cable 154183 to all NATO Capitals, "NPG: Discussion of Strategic Employment Doctrine," 11 June 1980, Secret

Source: National Archives, Record Group 59, Department of State Papers, Subject File of Edmund S. Muskie, 1963-1981, box 2, Allied Nuclear Strategy: PD-59 [hereinafter cited as Muskie file]

Before President Carter signed PD-59 in July 1980, Brown briefed major allies on targeting "doctrine" at a meeting of the NATO Nuclear Planning Group (NPG) in Norway. Starting with the premise that deterrence would persuade the Soviets that no use of nuclear weapons could produce "victory," Brown spoke of the need for plans for battlefield use of nuclear weapons and "relatively limited use," and of "less than all-out strikes" and the role of a survivable force that could strike "a broader set of industrial and economic targets" During the discussion Brown explained that if the "Soviets can be made to realize that a wide range of targets are open to attack, including their strategic forces and forces along the Chinese border, it should give them pause to think."

Document 11: William E. Odom to Zbigniew Brzezinski, "Targeting PD Briefing for the President," 24 July 1980, Top Secret

Source: JCL, National Security Adviser, Subject File, box 35, P[residential] D]irective] 59 [5/80-1/81]

Getting Brzezinski ready to brief President Carter on the PD, Odom noted that the Republican presidential platform "includes a lot of nuclear war-fighting doctrine" and the PD will "clarify our policy and leave no room for confusion." Odom observed that "you dragged Brown along on this PD" in the sense that it included White House innovations, in the sections on flexibility, targeting priorities, and acquisition policy. The memorandum to Carter, which Brzezinski initialed, suggested that the PD was a combination of old and new: "significant and important innovations in improving control and management of our new forces," but "not a totally new departure" because NSDM 242 also "sought more flexibility."

Document 12: William E. Odom to Zbigniew Brzezinski, "M-B-B Luncheon Item: Targeting," 5 August 1980, with Presidential Directive 59, "Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy," 25 July 1980, Top Secret, excised copy

Source: JCL, Brzezinski Collection, box 23, Meetings-Muskie/Brown 7/80-9/81

More than a month after Brown's NPG briefing, Carter signed PD-59, sending copies only to Vice President Mondale and Secretary of Defense Brown. On 5 August, in advance of a regular meeting with Brown and Muskie, Odom advised Brzezinski to tell Muskie about the directive and, for his convenience, attached a copy of it. What happened, however, was that Brown offered to brief Muskie about changes in nuclear policy, although it was not clear to Muskie that they involved a presidential directive [See Document 18 below].

The document that Carter had signed followed the broad outlines of Odom's 22 March 1980 memorandum. An earlier declassification on the Carter Library Web site revealed language about deterrence and the importance of improved C3I capabilities, and the need for exercises to test the new targeting system, but it is massively excised. Among the excised portions is the language about pre-planned options for attacking a broad range of targets--military, industrial, and leadership--including "Cuba, North Vietnam [sic[, and North Korea." The excised sentence probably refers to China, possibly removing the People's Republic from the SIOP altogether and relegating attack plans to U.S. unified commands. The language on launch-on-warning (LOW) had also been exempted. While refraining from an endorsement of LOW-it was not U.S. "policy"-a capability was nevertheless to be available in the form of "pre-planned options" for attacks by "vulnerable" ICBMs. As Odom had noted, this was a concession to Brown who sought such an option.

Also previously excised was the language on the importance of flexibility for designing targeting plans on "short notice" with appropriate staff capabilities in the military commands and the National Command Authority To permit post-attack options, a reserve force of the "most survivable and enduring strategic systems" was to be available against a "wide target spectrum." To make feasible the kind of war that Odom had envisaged, where tactical and strategic nuclear weapons supported conventional operations, the "major weight of the initial response" to Soviet nuclear use was to be on "military and control targets," including nuclear forces, command-and-control, stationary and mobile military forces, and industrial facilities that supported the military, with preplanned options available for political controls and "general industrial capability." Why this language was excised for so long is unclear because Secretary of Defense Brown's annual reports include specific references to the very same target categories. [12]

Document 14: Zbigniew Brzezinski to the President, "Flap with Muskie Over PD-59," n.d., Top Secret

Source: Library of Congress, William Odom Papers, box 36. Presidential Development re: Defense Policy Development White House 1977-1980 [1 of 2]

After the newspaper stories about Muskie's lack of knowledge about PD-59 appeared, Brzezinski had his say on the problem in a memo to President Carter. In part, he blamed the State Department for not informing Muskie about the targeting policy review, especially Secretary of Defense Brown's exposition of elements of it before the Nuclear Planning Group a few months earlier [See Document 10]. He acknowledged, however, that Brown was "somewhat slow" in briefing Muskie and that Brown had not shown him the "actual directive" before the story broke. While Brzezinski wrote that Brown had "briefed" Muskie, a White House document from later in the month indicated that the briefing did not get across the central point that there was a new presidential directive [See Document 18 below]. In any event, Brzezinski argued that the State Department should be kept out of matters involving the SIOP; it was far too sensitive for "diplomatists" and should not be "reviewed or discussed by those not authorized or required to deal with it."

Document 13: Assistant Secretary of State for Politico-Military Affairs Reginald Bartholomew, to Secretary of State Muskie, "U.S. Strategic Targeting Policy," 6 August 1980, Secret

Source: State Department FOIA release

Instead of learning about PD-59 from the White House, Muskie found out about it from the newspapers and he was probably furious. [13] A paper from Reginald Bartholomew provided Muskie with some background on the making of PD-59. While no one at the Department had seen the PD, Bartholomew believed that the press stories were generally accurate, although he suggested that the emphasis on military targeting as a "new feature" was misleading: "we have always included Soviet military targets in our plans."

Document 15: R. G. H. Seitz, Executive Secretariat, to Leon Fuerth, Office of the Counselor, 20 August 1980, enclosing paper from David Gombert, deputy director of Bureau of Politico-Military Affairs, to Eugene Martin, special assistant to Deputy Secretary of State Warren Christopher, "Evolution and Foreign Policy Consequences of New Nuclear Targeting Policy (PD-59)." 15 August 1980, Secret

Source: Muskie file

According to press reports, Brown sent a staffer to brief Muskie, and David Gompert from the State Department was also slated to fly to Maine to brief the Secretary about PD-59. [14] Muskie's deputy, Warren Christopher, had asked Gompert for more information and soon received a longish paper on the broad implications of PD-59. In part Gompert's paper was a critique of the news coverage which he thought was "overblown" by emphasizing PD-59 as an "abrupt and dramatic departure" instead of its "evolutionary" character. While Gompert believed that U.S. allies would support the "substance" of the PD as an effort to strengthen the credibility of deterrence by creating more options and adding greater flexibility, he knew that concepts of nuclear warfighting created nervousness in Western Europe. Noting Moscow's critical reactions, Gompert wondered if the reaction would have been different if the policy had not been leaked but broached in a more "responsible" manner.

According to press reports, the Pentagon asserted that it had kept the State Department informed [15], but Gompert described a policymaking process which excluded the Department's input at crucial stages. There had been no interagency analysis or discussion and both the Pentagon and the White House had "rebuffed" State Department efforts to follow up on the issues. Not surprisingly Gombert concluded that the Department should be involved in the "formulation and assessment of national security decisions that have significant foreign policy implications."

Document 16: Zbigniew Brzezinski to Secretary of Defense and Secretary of State, "PD-59 Chronology," 22 August 1980, enclosing chronology, Secret

Source: Muskie file

Brzezinski pushed back against State Department claims about being excluded from PD-59 by sending Brown and Muskie a chronology that glossed over the details that Gompert had discussed. The chronology included details on briefing of key reporters at the Times and the Washington Post and the efforts to spin the coverage, by muting whether Muskie was in the loop or not. While the chronology ended with the claim that "all of the agencies were involved" and there had been no "intention to exclude the Secretary of State," it showed that President Carter had made a choice not to include Muskie in an early briefing when he signed the PD, and that the State Department had no role in its actual preparation. [16]

Document 17: Marshall Shulman to Secretary of State Muskie, "PD-59," 2 September 1980, Secret

Source: Muskie file

Former Columbia University Professor Marshall Shulman, a leading Sovietologist who served as a special adviser on Soviet policy to Vance and Muskie, saw the PD-59 decision-making process as a "case study in how not to make national security policy." Because of the role of leaks and the non-role of the State Department, the "net effect of this episode was very negative." He had not seen the PD but questioned some of its assumptions. For example, on the notions that the Soviets had a concept of victory in nuclear war and already had limited nuclear options, "We may be placing more weight on the Soviet [military] literature than is warranted." If the Soviets perused U.S. military writing, it could "easily convince them that we have such options and such beliefs." Moreover, even if the Soviets had a concept of victory, it was worth asking whether an "imitative response … might make the problem worse." For example, the leaks emphasized the role of leadership and C3I targets in PD-59, which could "only increase Soviet perceptions of vulnerability" and introduce "further instability in the strategic balance."

Document 18: White House Counsel Lloyd Cutler to Leon [Fuerth], 4 September 1980, enclosing "Chronology of the PD-59 Decision," Top Secret

Source: Muskie file

Perhaps because of the complaints about the Brzezinski chronology, White House Counsel Lloyd Cutler prepared a new version, which Leon Fuerth passed on to Secretary Muskie with the comment that it appeared to be both "accurate and nonpolemical." For example, Brzezinski had claimed that "Brown had briefed Muskie" on 5 August, but the Cutler version has Brown offering to brief Muskie and that the latter did not "understand from discussion at this meeting that a PD is involved or that it has already been signed."

Document 19: Executive Secretary Peter Tarnoff to Secretary of State Muskie, "Your Breakfast with the President Friday, September 5, 1980," Item on PD-59, Secret

Source: National Archives, RG 59, Edmund Muskie Subject File, box 3, President's Breakfasts, July, August, September 1980

With Muskie going to appear on Face the Nation a few days after he was scheduled to meet President Carter on 5 September, it remained an "open question" why the White House had not informed the secretary of state of the signing of PD-59. State Department official Tarnoff saw the meeting with the president as an opportunity for "both of you to acknowledge that an oversight had been committed." Other open questions were whether Muskie can be "assured" that there will be "meaningful and timely" consultations between the Pentagon and the State Department and whether officials at the Department of State would see PD-59. The latter problem had "symbolic and substantive importance": either a copy of the PD should be on file at the State Department or senior officials should study it at the White House. What happened next is unclear. [17]

Document 20: Reg Bartholomew to Mr. Secretary, 5 September 1980, Secret

Source: Muskie file

Brzezinski sent a memorandum about PD-59 to Vice President Mondale and Secretary Muskie (it was not in the file) which, Bartholomew argued, "raises serious questions about the coherence of the Administration's internal understanding and public-line." In a recent speech at the Naval War College on the new strategy, Harold Brown had said that it was "not new," but the result of "evolutionary change"; for example, NSDM 242 had been one of the roots of the PD. In his memo, however, Brzezinski declared that it was the "third major revision of strategic doctrine since World War II," that it was "fundamentally different" from NSDM 242, and that the administration should get "public credit" for the change. This raised a number of problems; for example, arguing that PD-59 was a "'major revision'" made it "much more of it as a war-fighting doctrine than it is. There would be hell to pay with our allies if we went in this direction." Indeed, West German leaders might have been stunned if they knew that Secretary of Defense Brown had been, as Odom put it, "chasing" Warsaw Pact divisions with nuclear weapons during a military exercise.

Document 21: Secretary of Defense, "Policy Guidance for the Employment of Nuclear Weapons (NUWEP)," 24 October 1980, Top Secret, excised copy

Source: Department of Defense release, currently under appeal

While Brown and Brzezinski's advisers were reaching agreement on the language for PD-59, Pentagon officials were also drafting the detailed guidance for military planning that would be consistent with the directive and would further supplant the 1974 NUWEP. This heavily excised version excludes all language about target categories, but PD-59 helps fill in some of the blanks, for example, regarding "countervailing strategy" on pages 1 and 9, and "military and control targets" also on page 9. An excised heading on page 7 may refer to China.

Consistent with PD-59, the NUWEP emphasized flexibility, a capability to "design employment plans on short notice," and pre-planning, so that policymakers could respond "with selectivity to less than an all-out Soviet attack." A key element in both was the concept of "building blocks," which could be used as separate targeting options or could be combined to "provide larger and more comprehensive plans." Moreover, in keeping with the PD, the NUWEP included provisions for "endurance," reserve forces, periodic exercises to "test the suitability of implementing pre-planned and ad hoc nuclear weapons plans," and "continuing policy review."

NOTES

[1] In the absence of declassified information on PD-59, a number of studies on Carter administration security and foreign policy have had to rely on journalism and a handful of declassified and heavily excised documents. See for example, Betty Glad , An Outsider in the White House: Jimmy Carter, His Advisers, and the Making of American Foreign Policy (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2008), and Brian J. Auten, Carter's Conversion: The Hardening of American Foreign Policy (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2008). See also, for the first few years of the Carter administration, Olav Njҩlstad, The Peacekeeper and the Troublemaker: The Containment Policy of Jimmy Carter, 1977-1978 (Oslo, 1995).

For an informative account of the making of PD-59, see William E. Odom, "The Origins and Design of Presidential Decision-59: A Memoir," in Henry D. Sokolski, ed., Getting MAD: Nuclear Mutual Assured Destruction, Its Origins and Practice (Carlisle Barracks, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, 2004)

[2] For a partial exception, see Walter Pincus, "Thinking the Unthinkable: Studying New Approaches to Nuclear War, " The Washington Post , 11 February 1979, which provided a glimpse of some of the contract studies for the nuclear targeting review.

[3] See for example, George Wilson, "'Counterforce' Arms Attract U.S., Soviets: U.S., Soviets Developing 'Counterforce' To Destroy Each Other's Land Missiles ," The Washington Post, 1 June 1979.

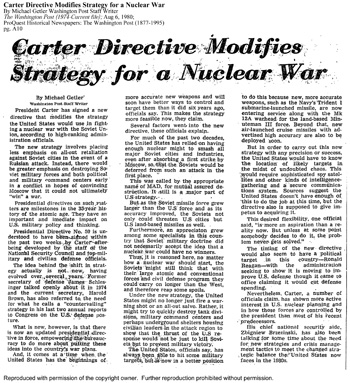

[4] Richard Burt, "Carter Said to Back a Plan for Limiting Nuclear War," The New York Times, 6 August 1980; George Wilson, "Carter Directive Modifies Strategy for a Nuclear War," The Washington Post, 6 August 1980.

[5] George Wilson, "U.S. Shift in Nuclear War Strategy Evokes Some Shudders," The Washington Post, 13 August 1980.

[7] This version of PD-18, made available to top Pentagon officials, may or may not be complete. The heavily excised version that has been available appears to be longer.

[8] John Hines, Ellis M. Mishulovich, and John F. Shulle, Soviet Intentions 1965-1985, Volume I: An Analytical Comparison of U.S.-Soviet Assessments During the Cold War, BDM Federal, Inc., September 22, 1995, Unclassified, excised copy.

[9] Erroneously, Odom credits the creation of the SIOP to Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara; but he inherited it from the Eisenhower administration. See David Alan Rosenberg, "The Origins of Overkill: Nuclear Weapons and American Strategy, 1945-1960," International Security 7 (1983). 3-71.

[10] Odom, "The Origins and Design of Presidential Decision-59," 193.

[11] For the risks of a launch-on-warning capability, see Bruce Blair, The Logic of Accidental Nuclear War (Washington D.C,, 1993)

[12] For details on target systems, see U.S. Department of Defense, Annual Report Fiscal Year 1979 (Washington, D.C. 1978), 55; U.S. Department of Defense, Report of Secretary of Defense Harold Brown to the Congress on the FY 1982 Budget, FY 1983 Authorization Request and FY 1982-1986 Defense Program (Washington, D.C.: 1981), 41-42.

[13] "Pentagon Says State Was Informed of Shift in A-War Strategy," The Washington Post, 11 August 1980.

[14] "Defense Dept. Sends Aide to Brief Muskie on Nuclear Strategy Policy," The New York Times, 12 August 1980.

[15] "Pentagon Says State Was Informed of Shift in A-War Strategy," The Washington Post, 11 August 1980.

[16] Brzezinski briefly discusses this problem in his memoir, Power and Principle: Memoirs of the National Security Adviser 1977-1981 (New York: Farrar Strauss Giroux, 1983) at pages 458-459, where he argues that Brown's delay in briefing Muskie had been "unintentional."

[17] President Carter's diary has brief references to PD-59 and the media controversy, but what has been published does not mention the meeting with Muskie. See Jimmy Carter, White House Diary (New York, 2010), 450 and 456.