|

|

|

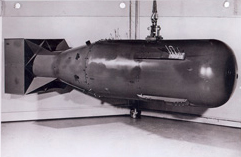

| A

nuclear weapon of the "Little Boy" type, the uranium gun-type

detonated over Hiroshima. It is 28 inches in diameter and

120 inches long. "Little Boy" weighed about 9,000 pounds and

had a yield approximating 15,000 tons of high explosives.

(Copy from U.S. National Archives, RG 77-AEC) |

Washington,

D.C., August 5, 2005 - Sixty years ago

this month, the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima

and Nagasaki, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan, and the Japanese

government surrendered to the United States and its allies. The

nuclear age had truly begun with the first military use of atomic

weapons. With the material that follows, the National Security Archive

publishes the most comprehensive on-line collection to date of declassified

U.S. government documents on the atomic bomb and the end of the

war in the Pacific. Besides material from the files of the Manhattan

Project, this collection includes formerly "Top Secret Ultra" summaries

and translations of Japanese diplomatic cable traffic intercepted

under the "Magic" program. Moreover, the collection includes for

the first time translations from Japanese sources of high level

meetings and discussions in Tokyo, including the conferences when

Emperor Hirohito authorized the final decision to surrender.[1]

|

| A

nuclear weapon of the "Fat Man" type, the plutonium implosion

type detonated over Nagasaki. 60 inches in diameter and 128

inches long, the weapon weighed about 10,000 pounds and had

a yield approximating 21,000 tons of high explosives (Copy

from U.S. National Archives, RG 77-AEC) |

Ever since the atomic bombs were exploded over Japanese cities,

historians, social scientists, journalists, World War II veterans,

and ordinary citizens have engaged in intense controversy about

the events of August 1945. John Hersey’s Hiroshima, first published

in the New Yorker in 1946 made some unsettled readers question

the bombings while church groups and a few commentators, most prominently

Norman Cousins, explicitly criticized them. Former Secretary of

War Henry Stimson found the criticisms troubling and published an

influential justification for the attacks in Harper’s.[2]

During the 1960s the availability of primary sources made historical

research and writing possible and the debate became more vigorous.

Historians Herbert Feis and Gar Alperovitz raised searching questions

about the first use of nuclear weapons and their broader political

and diplomatic implications. The controversy, especially the arguments

made by Alperovitz and others about "atomic diplomacy" quickly became

caught up in heated debates about Cold War "revisionism." The controversy

simmered over the years with major contributions by Martin Sherwin

and Barton J. Bernstein but it became explosive during the mid-1990s

when curators at the National Air and Space Museum met the wrath

of the Air Force Association over a proposed historical exhibit

on the Enola Gay.[3]

The NASM exhibit was drastically scaled down but historians and

journalists continued to engage in the debate. Alperovitz, Bernstein,

and Sherwin made new contributions to the debate as did historians,

social scientists, and journalists such as Richard B. Frank, Herbert

Bix, Sadao Asada, Kai Bird, Robert James Maddox, Robert P. Newman,

Robert S. Norris, Tsuyoshi Hagesawa, and J. Samuel Walker.[4]

The controversy has revolved around the following, among other,

questions:

|

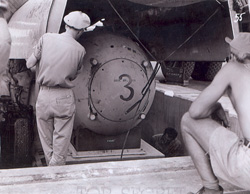

| Taken

at Tinian Island on the afternoon of August 5, 1945, this

shows the tail of the Enola Gay being edged over the pit and

into position to load "Little Boy" into the bomb bay. The

weapon is in the pit covered with canvas. Various personnel

and guards are standing around the loading area. (Photo from

U.S. National Archives, RG 77-BT) |

- Were atomic strikes necessary primarily to avert an invasion

of Japan in November 1945?

- Did Truman authorize the use of atomic bombs for diplomatic-political

reasons-- to intimidate the Soviets--or was his major goal to

force Japan to surrender and bring the war to an early end?

- If ending the war quickly was the most important motivation

of Truman and his advisers to what extent did they see an "atomic

diplomacy" capability as a "bonus"?

- To what extent did subsequent justification for the atomic bomb

exaggerate or misuse wartime estimates for U.S. casualties stemming

from an invasion of Japan?

- Were there alternatives to the use of the weapons? If there

were, what were they and how plausible are they in retrospect?

Why were alternatives not pursued?

- How did the U.S. government plan to use the bombs? What concepts

did war planners use to select targets? To what extent were senior

officials interested in looking at alternatives to urban targets?

How familiar was President Truman with the concepts that led target

planners to choose major cities as targets?

- Did President Truman make a decision, in a robust sense, to

use the bomb or did he inherit a decision that had already been

made?

- Were the Japanese ready to surrender before the bombs were dropped?

To what extent had Emperor Hirohito prolonged the war unnecessarily

by not seizing opportunities for surrender?

- If the United States had been more flexible about the demand

for "unconditional surrender" by guaranteeing a constitutional

monarchy would Japan have surrendered earlier than it did?

- How greatly did the atomic bombings affect the Japanese decision

to surrender?

- Was the bombing of Nagasaki unnecessary? To the extent that

the atomic bombing was critically important to the Japanese decision

to surrender would it have been enough to destroy one city?

- Would the Soviet declaration of war have been enough to compel

Tokyo to admit defeat?

- Was the dropping of the atomic bombs morally justifiable?

|

| This

shows the "Little Boy" weapon in the pit ready for loading

into the bomb bay of Enola Gay. (Photo from U.S. National

Archives, RG 77-BT) |

This briefing book will not attempt to answer these questions or

use primary sources to stake out positions on any of them. Nor will

it attempt to substitute for the extraordinarily rich literature

on the atomic bombs and the end of World War II. This collection

does not attempt to document the origins and development of the

Manhattan Project. Nor does it include any of the miscellaneous

sources (interviews, documents prepared after the events, post-World

War II correspondence, etc.) that participants in the debate have

brought to bear in framing their arguments. Instead, by gaining

access to a broad range of U.S. and Japanese documents from the

spring and summer of 1945, interested readers can see for themselves

the crucial source material that scholars have used to shape narrative

accounts of the historical developments and to frame their arguments

about the questions that have provoked controversy over the years.

To help readers who are less familiar with the debates, commentary

on some of the documents will point out, although far from comprehensively,

some of the ways in which they have been interpreted. With direct

access to the documents, readers may be able to develop their own

answers to the questions raised above. The documents may even provoke

new questions.

|

| This

shows "Little Boy" being raised for loading into the Enola

Gay's bomb bay. (Photo from U.S. National Archives, RG 77-BT) |

Contributors to the historical controversy have deployed the documents

selected here to support their arguments about the first use of

nuclear weapons and the end of World War II. The editor has closely

reviewed the footnotes and endnotes in a variety of articles and

books and selected documents cited by participants on the various

sides of the controversy.[5]

While the editor has a point of view on the issues, to the greatest

extent possible he has tried not to let that influence document

selection, e.g., by selectively withholding or including documents

that may buttress one point of view or the other. The task of compilation

took the editor to primary sources at the National Archives, mainly

in Manhattan Project files held in the records of the Army Corps

of Engineers, Record Group 77 but also in the files of the National

Security Agency. Private collections were also important such as

the Stimson Diary at Yale University (although available on microfilm

elsewhere) and the papers of W. Averell Harriman at the Library

of Congress. To a great extent the documents selected for this compilation

have been declassified for years, even decades; the most recent

declassifications were in the 1990s.

|

| The

mushroom cloud billowing up 20,000 feet over Hiroshima on

the morning of August 6, 1945 (Photo from U.S. National Archives,

RG 77-AEC) |

The U.S. documents cited here will be familiar to many expert readers

on the Hiroshima-Nagasaki controversy. To provide a fuller picture

of the transition from U.S.-Japanese antagonism to reconciliation,

the editor has done what could be done within time and resource

constraints to present information on the activities and points

of view of Japanese policymakers and diplomats. This includes a

number of formerly top secret summaries of intercepted Japanese

diplomatic communications; the documents enable interested readers

to form their own judgments about the direction of Japanese diplomacy

in the weeks before the atomic bombings. Moreover, this briefing

book includes new translations of Japanese primary sources on crucial

events, including accounts of the conferences on August 9 and 14,

where Emperor Hirohito made decisions to accept Allied terms of

surrender. This material sheds light on the considerations that

induced Japan ’s surrender.

Documents

Note: The following documents are in PDF format.

You will need to download and install the free Adobe

Acrobat Reader to view. I.

Background on the Atomic Project

Document

1: Memorandum from Vannevar Bush and James B. Conant, Office

of Scientific Research and Development, to Secretary of War, September

30, 1944, Top Secret

Source:

Record Group 77, Records of the Army Corps of Engineers (hereinafter

RG 77), Manhattan Engineering District (MED), Harrison-Bundy Files

(H-B Files), folder 69

Months before the bomb would be available, key War Department advisers,

among others, worried about the political and military problems

and possibilities raised by the project—the possibility of enormously

powerful hydrogen bombs, enormous military potential, the limits

of secrecy, the danger of a global arms race, and the need for international

exchange of information and international inspection to stem dangerous

nuclear competition. Martin Sherwin and James Hershberg see this

memorandum flowing from Bush and Conant’s concern about President

Roosevelt's "cavalier" belief that it would be possible

to maintain an Anglo-American atomic monopoly after World War II.

To disabuse senior officials that such a monopoly was possible,

they drafted this memorandum.[6]

|

| The

Enola Gay returns to Tinian Island after the strike on Hiroshima.

(Photo from U.S. National Archives, RG 77-BT) |

Document

2: Commander F. L. Ashworth to Major General L.R. Groves, "The

Base of Operations of the 509th Composite Group,"

February 24, 1945, Top Secret

Source:

RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File no. 5g

The force of B-29 nuclear delivery vehicles that

was being readied for first nuclear use—the Army Air Force’s 509th

Composite Group—required an operational base in the Western Pacific.

In late February 1945, months before atomic bombs were ready for

use, the high command selected Tinian, an

island in the Northern

Marianas Islands.

Documents

3a-c: President Truman Learns the Secret:

a.

Memorandum for the Secretary of War from General L. R. Groves, "Atomic

Fission Bombs," April 23,

1945

Source: RG 77, Commanding General’s file no. 24, tab

D

b.

Memorandum discussed with the President, April 25, 1945

Source:

Henry Stimson Diary, Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library,

Henry Lewis Stimson Papers (microfilm at Library of Congress)

c.

Untitled memorandum by General L.R. Groves, April 25, 1945

Source: Record Group 200, Papers of General Leslie R.

Groves, Correspondence 1941-1970,

box

3, "F"

d.

Diary Entry, April 25,

1945

Source: Henry Stimson Diary, Sterling

Library, Yale

University

(microfilm at Library of Congress)

|

| A

"Fat Man" test unit being raised from the pit into the bomb

bay of a B-29 for bombing practice during the weeks before

the attack on Nagasaki. (Photo from U.S. National Archives,

RG 77-BT) |

Soon after he was sworn in as president, after

President Roosevelt's death, Harry Truman learned about the top

secret Manhattan Project. It

was not until he received a briefing from Secretary of War Stimson

and Manhattan Project chief General

Groves, who went through

the "back door" to escape the watchful press, that Truman

understood the full scope of the enterprise.

Stimson, who later wrote up the meeting in his diary, also

prepared a discussion paper, which raised broader policy issues

associated with the imminent possession of "the most terrible

weapon ever known in human history."

In a background report prepared for the meeting, Groves

provided a detailed overview of the atomic bomb project from the

raw materials to processing nuclear fuel to assembling the weapons

to plans for using them, which had already crystallized. With

respect to the last point, the first gun-type weapon "should

be ready about 1 August 1945" while an implosion weapon would

be available that month. "The target is and was always expected to

be Japan." The question

whether Truman “inherited assumptions” from the Roosevelt

administration that the bomb would be used has been a controversial

one. Alperovitz and Sherwin have argued that Truman

made "a real decision" to use the bomb on Japan

by choosing "between various forms of diplomacy and warfare." In contrast, Barton Bernstein finds that Truman

"never questioned [the] assumption" that the bomb would

and should be used. Robert

S. Norris has also noted that "Truman’s 'decision' was a decision

not to override previous plans to use the bomb."[7]

II.

Defining Targets

Document

4: Notes on Initial Meeting of Target Committee, May 2, 1945, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File

no. 5d (copy from microfilm)

|

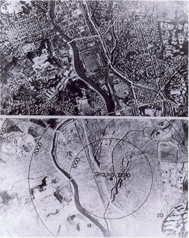

| A

photo prepared by U.S. Air Intelligence for analytical work

on destructiveness of atomic weapons. The total area devastated

by the atomic strike on Hiroshima is shown in the darkened

area (within the circle) of the photo. The numbered items

are military and industrial installations with the percentages

of total destruction. (Photo from U.S. National Archives,

RG 77-AEC) |

In late April, military officers and nuclear scientists

met to discuss bombing techniques, target selection, and overall

mission requirements. The

discussion of "available targets" included Hiroshima,

the "largest untouched targets not on the 21st Bomber

Command priority list."

Document

5: Memorandum from J. R. Oppenheimer to Brigadier General Farrell,

May 11, 1945

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File

no. 5g (copy from microfilm)

Discussing the radiological dangers of a nuclear

detonation, Oppenheimer explained to General Farrell, Groves's

deputy, the need for precautions.

Document

6: Memorandum from Major J. A. Derry and Dr. N.F. Ramsey to

General L.R. Groves, "Summary of Target Committee Meetings

on 10 and 11 May 1945," May 12, 1945, Top

Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File

no. 5d (copy from microfilm)

Scientists and officers held further discussion

of bombing mission requirements, including height of detonation,

weather, plans for possible mission abort, and the various aspects

of target selection, including priority cities ("a large urban

area of more than three miles diameter") and psychological

dimension.

Document

7: Diary Entries, May 14 and 15, 1945

Source:

Henry Stimson Diary, Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library,

Henry Lewis Stimson Papers (microfilm at Library of Congress)

|

| The

polar cap of the "Fat Man" weapon being sprayed with plastic

spray paint in front of Assembly Building Number 2. (Photo

from U.S. National Archives, RG 77-BT) |

On May 14 and 15, Stimson had several conversations

involving S-1 (the atomic bomb); during a talk with Assistant Secretary

of War John J. McCloy, he estimated that possession of the bomb

gave Washington a tremendous advantage—"held all the cards,"

a "royal straight flush"-- in dealing with Moscow on post-war

problems: "They can’t get along without our help and industries

and we have coming into action a weapon which will be unique."

The next day a discussion of divergences with Moscow

over the Far East made Stimson wonder whether

the atomic bomb would be ready when Truman met with Stalin in July. If it was, he believed that the bomb would be

the "master card" in U.S.

diplomacy. This and other

entries from the Stimson diary (as well as the entry from the Davies

diary that follows) are important to arguments developed by Gar

Alperovitz and Barton J. Bernstein, among others, although with

significantly different emphases, that in light of controversies

with the Soviet Union over Eastern Europe and other areas, top officials

in the Truman administration believed that possessing the atomic

bomb would provide them with significant leverage for inducing Moscow’s

acquiescence in U.S. objectives.[8]

Document

8: Diary entry for May 21, 1945

Source: Joseph E. Davies Papers, Library of Congress,

box

17, 21 May 1945

While officials at the Pentagon continued to look

closely at the problem of atomic targets, President Truman, like

Stimson, was thinking about the diplomatic implications of the bomb.

During a conversation with Joseph E. Davies, a prominent

Washington lawyer

and former ambassador to the Soviet Union,

Truman said that he wanted to delay talks with Stalin and Churchill

until July when the first atomic device would have been tested.

Alperovitz treats this entry as evidence in support of the atomic

diplomacy argument, but other historians, ranging from Robert Maddox

to Gabriel Kolko, deny that the timing of the Potsdam

conference had anything to do with the goal of using the bomb to

intimidate the Soviets.[9]

Document

9: Minutes of Third Target Committee Meeting – Washington, May 28, 1945, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File

no. 5d (copy from microfilm)

More updates on training missions, target selection,

and conditions required for successful detonation over the target.

“Pumpkins” referred to bright orange, pumpkin-shaped high explosive

bombs—shaped like the “Fat Man” implosion weapon--used for bombing

run test missions.

Document

10: General Lauris Norstad to Commanding General, XXI Bomber

Command, "509th Composite Group; Special Functions,"May 29, 1945, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File

no. 5g (copy from microfilm)

The 509th Composite Group’s cover story

for its secret mission was the preparation of “Pumpkins” for use

in battle. In this memorandum, Norstad reviewed the complex

requirements for preparing B-29s and their crews for successful

nuclear strikes.

Document

11: Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy, "Memorandum

of Conversation with General Marshall May 29, 1945 –

11:45 p.m.," Top Secret

Source: Record Group 107, Office of the Secretary of

War, Formerly Top Secret Correspondence of Secretary of War Stimson

(“Safe File”), July 1940-September 1945, box 12, S-1

Apparently dissenting from the Targeting Committee’s

recommendations, Army Chief of Staff George Marshall noted the “opprobrium

which might follow from an ill considered employment of such force.” This document has played a role in arguments

developed by Barton J. Bernstein that a few figures such as Marshall

and Stimson were “caught between an older morality that opposed

the intentional killing of noncombatants and a newer one that stressed

virtually total war.”[10]

Document

12: "Notes of the Interim Committee Meeting Thursday, 31

May 1945, 10:00 A.M. to 1:15 P.M. – 2:15 P.M. to 4:15 P.M.,"

n.d., Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, H-B files, folder no. 100

(copy from microfilm)

With Secretary of War Stimson presiding, members

of the committee heard reports on a variety of Manhattan Project

issues, including the stages of development of the atomic project,

problems of secrecy, the possibility of informing

the Soviet Union, cooperation with “like-minded” powers, the military

impact of the bomb on Japan, and the problem of “undesirable scientists.”

Interested in producing the “greatest psychological

effect,” the Committee members agreed that the “most desirable target

would be a vital war plant employing a large number of workers and

closely surrounded by workers’ houses.”

Bernstein argues that this target choice represented an uneasy

endorsement of “terror bombing”--the target was not exclusively

military or civilian; nevertheless, workers' housing would include

noncombatant men, women, and children.[11]

Document

13: General George A. Lincoln to General Hull, June 4, 1945, enclosing draft, Top Secret

Source: Record Group 165, Records of the War Department

General and Special Staffs, American-British-Canadian Top Secret

Correspondence, Box 504,

ABC 387 Japan (15

Feb. 45)

George A. Lincoln, chief of the Strategy and Policy

Group at the U.S. Army’s Operations Department, commented on a memorandum

by former President Herbert Hoover that Stimson had passed on for

analysis. Hoover

proposed a compromise solution with Japan

that would allow Tokyo

to retain part of its empire in East Asia

(including Korea

and Japan)

as a way to head off Soviet influence in the region. While

Lincoln

believed that the proposed peace teams were militarily acceptable

he doubted that they were workable or that they could check Soviet

“expansion” which he saw as an inescapable result of World War II.

As to how the war with Japan

would end, he saw it as “unpredictable” but speculated about “Russian

entry into the war, combined with a landing, or imminent threat

of a landing, on Japan

proper by us, to convince them of the hopelessness of their situation.”

Lincoln derided

Hoover’s

casualty estimate of 500,000. J.

Samuel Walker has cited this document to make the point that “contrary

to revisionist assertions, American policymakers in the summer of

1945 were far from certain that the Soviet invasion of Manchuria

would be enough in itself to force a Japanese surrender.”[12]

Document

14: Memorandum from R. Gordon Arneson, Interim Committee Secretary,

to Mr. Harrison, June 6, 1945, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, H-B files, folder no. 100

(copy from microfilm)

In a memorandum to George Harrison, Stimson’s special

assistant on Manhattan Project matters, Arneson noted actions taken

at the recent Interim Committee meetings, including target criteria

and an attack “without prior warning.”

Document

15: Memorandum of Conference with the President,

June 6, 1945,

Top Secret

Source:

Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library, Henry Lewis Stimson

Papers (microfilm at Library of Congress)

Stimson and Truman began this meeting by discussing

how they should handle a conflict with French President deGaulle

over the movement by French forces into Italian territory. (Truman

finally cut off military aid to France

to compel the French to pull back).[13] As evident

from the discussion, Stimson strongly disliked de Gaulle, whom he

regarded as “psychopathic.” The

conversation soon turned to the atomic bomb, with some discussion

about plans to inform the Soviets but only after a successful test. Both agreed that the possibility of a nuclear

“partnership” with Moscow

would depend on “quid pro quos”: “the settlement of the Polish,

Rumanian, Yugoslavian, and Manchurian problems.”

At the end, Stimson shared his doubts about targeting cities

and killing civilians through area bombing because of its impact

on the U.S.’s

reputation as well as on the problem of finding targets for the

atomic bomb. Barton Bernstein

has also pointed to this as additional evidence of the influence

on Stimson of “an older morality.”

III.

Debates on Alternatives to First Use and Unconditional Surrender

Document

16: Memorandum from Arthur B. Compton to the Secretary of War,

enclosing "Memorandum on 'Political and Social Problems,' from

Members of the 'Metallurgical Laboratory' of the

University of Chicago," June 12, 1945, Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, H-B files, folder no. 76

(copy from microfilm)

Physicists Leo Szilard and James Franck, a Nobel

Prize winner, were on the staff of the “Metallurgical Laboratory”

at the University of

Chicago,

a cover for the Manhattan Project program to produce fuel for the

bomb. The outspoken Szilard was not involved in operational

work on the bomb and General Groves kept him under surveillance,

but Met Lab director found Szilard useful to have around. Concerned with the long-run implications of

the bomb, Franck chaired a committee, in which Szilard and Eugene

Rabinowitch were major contributors, that produced a report rejecting

a surprise attack on Japan and recommended instead a demonstration

of the bomb on the “desert or a barren island.”

Arguing that a nuclear arms race “will be on in earnest not

later than the morning after our first demonstration of the existence

of nuclear weapons,” the committee saw international control as

the alternative. That possibility

would be difficult if the United

States made first military use

of the weapon. Arthur Compton,

the “Met Lab’s” director, raised doubts about the recommendations

but urged Stimson to study the report. Martin

Sherwin has argued that the Franck committee shared an important

assumption with Truman et al.--that an “atomic attack against Japan

would 'shock' the Russians”--but drew entirely different conclusions

about the import of such a shock.[14]

Document

17: Memorandum from Acting Secretary of State Joseph Grew to

the President, "Analysis of Memorandum Presented by Mr.

Hoover,"

June 13, 1945

Source: Record Group 107, Office of the Secretary of

War, Formerly Top Secret Correspondence of Secretary of War Stimson

("Safe File"), July 1940-September 1945, box 8, Japan

(After December 7/41)

A former ambassador to Japan,

Grew’s knowledge of Japanese politics and culture informed his critical

stance toward the concept of unconditional surrender.

He believed it essential that the United

States declare its intention to

preserve the institution of the emperor.

As he argued in this memorandum to President Truman, “failure

on our part to clarify our intentions” on the status of the emperor

“will insure prolongation of the war and cost a large number of

human lives.” Documents like

this have played a role in arguments developed by Alperovitz that

Truman and his advisers had alternatives to using the bomb such

as modifying unconditional surrender and that anti-Soviet considerations

weighed most heavily in their thinking. By

contrast, Herbert P. Bix has argued that the Japanese leadership

would “probably not” have “surrendered if the Truman administration

had clarified the status of the emperor” when it demanded unconditional

surrender.[15]

Document

18: Memorandum from Chief of Staff Marshall to the Secretary

of War, 15 June 1945, enclosing "Memorandum of Comments on

'Ending the Japanese War,'" June 14, 1945

Source: Record Group 107, Office of the Secretary of

War, Formerly Top Secret Correspondence of Secretary of War Stimson

("Safe File"), July 1940-September 1945, box 8, Japan

(After December 7/41)

Commenting on another memorandum by Herbert Hoover,

George A. Lincoln discussed war aims, face-saving proposals for

Japan,

and the nature of the proposed declaration to the Japanese government,

including the problem of defining “unconditional surrender.” Lincoln

argued against modifying the concept of unconditional surrender:

if it is “phrased so as to invite negotiation” he saw risks of prolonging

the war or a “compromise peace.”

J. Samuel Walker has observed that those risks help explain

why senior officials were unwilling to modify the demand for unconditional

surrender.[16]

Document

19: Memorandum by J. R. Oppenheimer, "Recommendations on

the Immediate Use of Nuclear Weapons," June 16, 1945,

Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, H-B files, folder no. 76

(copy from microfilm)

In a report to Stimson, Oppenheimer and colleagues

on the scientific advisory panel--Arthur Compton, Ernest O. Lawrence,

and Enrico Fermi--tacitly disagreed with the report of the “Met

Lab” scientists. The panel argued for early military use but

not before informing key allies about the atomic project to open

a dialogue on “how we can cooperate in making this development contribute

to improved international relations.”

Document

20: "Minutes of Meeting Held at the White House on Monday,

18 June 1945 at 1530," Top Secret

Source: Record Group 218, Records of the Joint Chiefs

of Staff, Central Decimal Files, 1942-1945,

box

198 334 JCS

(2-2-45)

Mtg 186th-194th

With the devastating battle for Okinawa

winding up, Truman and his military advisers stepped back and considered

the implications and requirements of the invasion of Japan.

In this meeting with the Joint Chiefs of Staff Truman reviewed plans

to land troops on Kyushu on 1 November, heard

a range of casualty estimates, and contemplated the possible impact

of eventual Soviet entry into the war with Japan.

This account hints at discussion of the atomic bomb (“certain other

matters”) but no documents disclose that part of the meeting.

This document has figured in the highly complex debate over

the estimates of casualties stemming from a possible invasion of

Japan. While post-war justifications for the bomb suggested

that an invasion of Japan

could have produced very high levels of casualties (dead, wounded,

or missing), from hundreds of thousands to a million, historians

have vigorously debated the extent to which the post-war estimates

were inflated.[17]

This meeting has also played a role in the historical

discussions of the alternatives to nuclear weapons use in the summer

of 1945. According

to accounts based on post-war recollections and interviews, McCloy

raised the possibility of winding up the war by guaranteeing the

preservation of the emperor albeit as a constitutional monarch.

If that failed to persuade Tokyo,

he proposed that the United States

disclose the secret of the atomic bomb to secure Japan’s

unconditional surrender. While McCloy later recalled that Truman

expressed interest, he said that Secretary of State Byrnes quashed

the proposal because of his opposition to any “deals” with Japan. Yet, according to Forrest Pogue’s account, when

Truman asked McCloy if he had any comments, the latter opened up

a discussion of nuclear weapons use by asking “Why not use the bomb?”[18]

Document

21: Memorandum from R. Gordon Arneson, Interim Committee Secretary,

to Mr. Harrison, June 25,

1945, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, H-B files, folder no. 100

(copy from microfilm)

For Harrison’s

convenience, Arneson summarized key decisions made at the 21 June

meeting of the Interim Committee, including a recommendation that

President Truman use the forthcoming conference of allied leaders

to inform Stalin about the atomic project. The Committee also reaffirmed

earlier recommendations about the use of the bomb at the “earliest

opportunity” and urban-industrial targets. In addition, it recommended revocation of part

two of the 1944 Quebec

agreement which stipulated that neither the United

States nor Great

Britain would use the bomb “against

third parties without each other’s consent.”

Thus, an impulse for unilateral control of nuclear use decisions

predated the first use of the bomb.[19]

Document

22: Memorandum from George L. Harrison to Secretary of War,

June 26, 1945, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED, H-B files, folder no. 77 (copy from

microfilm)

Reminding Stimson about the objections of some

Manhattan project scientists

to military use of the bomb, Harrison summarized

the basic arguments of the Franck report. One recommendation shared by many of the scientists,

whether they supported the Franck report or not, was that the United

States should inform Stalin about

the bomb before it was used. This

proposal had been the subject of positive discussion by the Interim

Committee on the grounds that Soviet confidence was necessary to

make possible post-war cooperation on atomic energy.

Document

23: Memorandum from George L. Harrison to Secretary of War,

June 28, 1945, Top Secret, enclosing Ralph Bard "Memorandum

on the Use of S-1 Bomb," June 27, 1945

Source: RG 77, MED, H-B files, folder no. 77 (copy from

microfilm)

Under Secretary of the Navy Ralph Bard joined those

scientists who sought to avoid military use of the bomb; he proposed

a “preliminary warning” so that the United

States would retain its position

as a “great humanitarian nation.” Alperovitz cites evidence that Bard discussed

his proposal with Truman who told him that he had already thoroughly

examined the problem of advanced warning. This document has also

figured in the argument framed by Barton Bernstein that Truman and

his advisers took it for granted that the bomb was a legitimate

weapon and that there was no reason to explore alternatives to military

use. Berstein, however, notes

that Bard later denied that he had a meeting with Truman and that

White House appointment logs support that claim.[20]

Document

24: Memorandum for Mr. McCloy, "Comments re: Proposed Program

for Japan," June 28, 1945, Draft, Top Secret

Source: RG 107, Office of Assistant Secretary of War

Formerly Classified Correspondence of John J. McCloy, 1941-1945,

box

38, ASW 387

Japan

Despite the interest of some senior officials such

as Joseph Grew, Henry Stimson, and John J. McCloy in modifying the

concept of unconditional surrender so that the Japanese could be

sure that the emperor would be preserved, it remained a highly contentious

subject. For example, one of McCloy’s staffers, Colonel Fahey, argued

against modification of unconditional surrender (see “Appendix ‘C`”).

Document

25: Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy to Colonel Stimson,

June 29, 1945, Top Secret

Source: Record Group 107, Office of the Secretary of

War, Formerly Top Secret Correspondence of Secretary of War Stimson

("Safe File"), July 1940-September 1945, box 8, Japan

(After December 7/41)

McCloy was part of a drafting committee that was

working on the text of a proclamation to Japan

which would be signed by heads of state at the forthcoming

Potsdam

conference. As McCloy observed

the most contentious issue was whether the proclamation should include

language about the preservation of the emperor: “This may cause

repercussions at home but without it those who seem to know the

most about Japan

feel there would be very little likelihood of acceptance.”

Document

26: Memorandum, "Timing of Proposed Demand for Japanese

Surrender," June 29, 1945, Top Secret

Source: Record Group 107, Office of the Secretary of

War, Formerly Top Secret Correspondence of Secretary of War Stimson

("Safe File"), July 1940-September 1945, box 8, Japan

(After December 7/41)

Probably the work of General George A. Lincoln

at Army Operations, this document was prepared a few weeks before

the Potsdam conference

when senior officials were starting to finalize the text of the

declaration that Truman, Churchill, and Chiang would issue there. The author recommended issuing the declaration

“just before the bombardment program [against Japan]

reaches its peak.” Next to

that suggestion, Stimson, or someone in his immediate office, wrote

“S1”, implying that the atomic bombing of Japanese cities was highly

relevant to the timing issue. Also

relevant to Japanese thinking about surrender, the author speculated,

was the Soviet attack on their forces after a declaration of war.

Document

27: Minutes, Secretary's Staff Committee, Saturday Morning,

July 7, 1945, 133d Meeting, Top Secret

Source: Record Group 353, Records of Interdepartmental

and Intradepartmental Committees, Secretary's Staff Meetings Minutes,

1944-1947 (copy from microfilm)

The possibility of modifying the concept of unconditional

surrender so that it guaranteed the continuation of the emperor

remained hotly contested within the U.S.

government. Here senior State Department officials, Under Secretary

Joseph Grew on one side, and Assistant Secretary Dean Acheson and

Archibald MacLeish on the other, engage in hot debate.

Document

28: Combined Chiefs of Staff, “Estimate of the Enemy Situation

(as of 6 July 1945, C.C.S 643/3, July 8, 1945, Secret (Appendices Not Included)

Source: RG 218, Central Decimal Files, 1943-1945, CCS

381 (6-4-45),

Sec. 2 Pt. 5

This review of Japanese capabilities and intentions

portrays an economy and society under “tremendous strain”; nevertheless,

“the ground component of the Japanese armed forces remains Japan’s

greatest military asset.” Alperovitz

sees statements in this estimate about the impact of Soviet entry

into the war and the possibility of a conditional surrender involving

survival of the emperor as an institution as more evidence that

the policymakers saw alternatives to nuclear weapons use.

By contrast, Richard Frank takes note of the estimate’s depiction

of the Japanese army’s terms for peace: “for surrender to be acceptable

to the Japanese army it would be necessary for the military leaders

to believe that it would not entail discrediting the warrior tradition

and that it would permit the ultimate resurgence of a military in

Japan.” That, Frank argues, would have been “unacceptable

to any Allied policy maker”.[21]

IV.

The Japanese Search for Soviet Mediation

Document

29: "Magic" – Diplomatic Summary, War Department,

Office of Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, No. 1204 – July 12, 1945,

Top Secret Ultra

Source: Record Group 457, Records of the National Security

Agency/Central Security Service, "Magic" Diplomatic Summaries

1942-1945, box

18

Since September 1940, under the covername "Magic,"

U.S. military intelligence had been routinely decrypting the intercepted

cable traffic of the Japanese Foreign Ministry. The National Security

Agency kept the 'Magic" diplomatic and military summaries classified

for many years and did not release the series for 1942 through August

1945 in its entirety until the early 1990s. This summary includes

a report on a cable from Japanese Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo

to Ambassador Naotake Sato in Moscow concerning the emperor's decision

to seek Soviet help in ending the war. Not knowing that the Soviets

had already made a commitment to its Allies to declare war on Japan,

Tokyo fruitlessly pursued this option for several weeks. The "Magic"

intercepts from mid-July have figured in Gar Alperovitz's argument

that Truman and his advisers recognized that the emperor was ready

to capitulate if the Allies showed more flexibility on the demand

for unconditional surrender. This point is central to Alperovitz's

thesis that top U.S. officials recognized a "two-step logic"

that moderating unconditional surrender and a Soviet declaration

of war would have been enough to induce Japan's surrender without

the use of the bomb.[22]

Document

30: John Weckerling, Deputy Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, July

12, 1945, to Deputy Chief of Staff, "Japanese Peace Offer,"

13 July 1945, Top Secret Ultra

Source: RG 165, Army Operations OPD Executive File #17,

Item 13 (copy courtesy of J. Samuel Walker)

The day after the Togo

message was reported, Army intelligence chief Weckerling proposed

several possible explanations of the Japanese diplomatic initiative.

Robert J. Maddox has cited this document to support his argument

that top U.S.

officials recognized that Japan

was not close to surrender because Japan

was trying to “stave off defeat.”

Having analyzed the document closely, Tsuyoshi Hasegawa argues

that each of the three possibilities proposed by Weckerling “contained

an element of truth, but none was entirely correct”.

For example, the “governing clique” that supported the peace

moves was not trying to “stave off defeat” but was seeking Soviet

help to end the war.[23]

Document

31: "Magic"– Diplomatic Summary, War Department, Office

of Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, No. 1205 – July 13, 1945, Top

Secret Ultra

Source: Record Group 457, Records of the National Security

Agency/Central Security Service, "Magic" Diplomatic Summaries

1942-1945, box

18

The day after he told Sato about the current thinking

on Soviet mediation, Togo requested the Ambassador to see Soviet

Foreign Minister Molotov and tell him of the emperor’s “private

intention to send Prince Konoye as a Special Envoy” to Moscow.

Before he received Togo’s

message, Sato had already met with Molotov on another matter.

Document

32: Cable to Secretary of State from Acting Secretary Joseph

Grew, July 16, 1945, Top Secret

Source: Record Group 59, Decimal Files 1945-1949, 740.0011

PW (PE)/7-1645

The draft of the proclamation to Japan that reached

Truman contained language that modified unconditional surrender

by promising to retain the emperor.

When former Secretary of State Cordell Hull learned about

that development he outlined his objections to Secretary of State

Byrnes. The latter was already inclined to reject that part of the

draft but Hull’s arguments

may have reinforced his decision.

Document

33: "Magic"

– Diplomatic Summary, War Department, Office of Assistant Chief

of Staff, G-2, No. 1210 – July 17, 1945, Top Secret Ultra

Source: Record Group 457, Records of the National Security

Agency/Central Security Service, "Magic" Diplomatic Summaries

1942-1945, box

18.

Another intercept of a cable from Togo

to Sato shows that the Foreign Minister rejected unconditional surrender

and that the emperor was not “asking the Russian’s mediation in

anything like unconditional surrender.”

Incidentally, this “Magic’ Diplomatic Summary” indicates

the broad scope and capabilities of the program; for example, it

includes translations of intercepted French messages (see pages

8-9). [Page 14 missing from original]

Document

34: R. E. Lapp, Leo Szilard et al., "A Petition to the

President of the United States," July 17, 1945

Source: RG 77, MED Records, H-B files, folder no. 76

(copy from microfilm)

In a final effort to discourage military use of

the bomb, Szilard circulated a petition, which he hoped would reach

President Truman, and which was signed by about 68 Manhattan Project

scientists, mainly physicists and biologists (copies with the remaining

signatures are in the archival file). Not

explicitly rejecting military use, the petition raised questions

about an arms race that military use could inspire and called Truman

to publicize detailed terms for Japanese surrender.

Truman, already on his way to Europe,

never saw the petition.[24]

V.

The Trinity Test, the

Potsdam Conference, and the Execution Order

Document

35: Cable War 33556 from Harrison to Secretary of War, July 17,

1945, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File

5e (copy from microfilm)

An elated message from Harrison

to Stimson reported on the success of the "Trinity" test

of a plutonium implosion weapon.

The light from the explosion could been seen “from here [Washington,

D.C.] to “high hold” [Stimson’s estate on Long Island—250 miles

away]” and it was so loud

that Harrison could have heard the “screams” from Washington, D.C.

to “my farm” [in Upperville, VA, 50 miles away][25]

Document

36: Memorandum

from General L. R. Groves to Secretary of War, "The Test,"

July 18,

1945, Top

Secret, Excised Copy

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File

no. 4 (copy from microfilm)

The first

atomic test took place in the New Mexico

desert on 16 August. General

Groves prepared for Stimson, then at Potsdam,

a detailed account of the “Trinity” test.[26]

Document

37: Diary Entry for July 20, 1945:

Source: Takashi

Itoh, ed., Sokichi Takagi:

Nikki to Joho [Sokichi Takagi: Diary and Documents] (Tokyo,

Japan:

Misuzu-Shobo, 2000), 916-917 [Translation by Hikaru Tajima]

In 1944 Navy minister Mitsumasa Yonai put rear

admiral Sokichi Takagi on sick leave so that he could undertake

a secret mission to find a way to end the war. Takaki was soon at

the center of a cabal of Japanese defense officials, civil servants,

and academics, which concluded that, in the end, the emperor would

have to “impose his decision on the military and the government.”

Takagi kept a detailed account of his activities, part of

which was in diary form, the other part of which he kept on index

cards. The material that

follows gives a sense of the state of play for Foreign Minister

Togo’s

attempt to secure Soviet mediation. Hasegawa cites it and other documents to make

a larger point about the inability of the Japanese government to

agree on “concrete” proposals to negotiate an end to the war.[27] The last item discusses Japanese contacts with

representatives of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in Switzerland.

The reference to “our contact”

may refer to Bank of International Settlements economist Pers Jacobbson

who was in contact with Japanese representatives to the Bank as

well as Gero von Gävernitz, then on the staff, but with non-official cover,

of OSS station chief Allen Dulles. The contacts never went far and Dulles never

received encouragement to pursue them.[28]

Document

38: Truman's

Potsdam Diary

Barton

J. Bernstein, "Truman At Potsdam:

His Secret Diary," Foreign Service Journal, July/August 1980, excerpts, used with author’s

permission[29]

Some years after Truman died a hand-written diary

that he kept during the Potsdam

conference surfaced in his personal papers. For

convenience Barton Bernstein’s rendition is provided here but linked

here are the scanned versions of Truman’s handwriting on the Truman

Library’s web site (for 16

July and 17-30

July respectively).

The diary entries cover July

16, 17, 18, 20, 25, 26, and 30 and include Truman’s thinking about

a number of issues and developments, including his reactions to

Churchill and Stalin, the atomic bomb and how it should be targeted,

the possible impact of the bomb and a Soviet declaration of war

on Japan, and his decision to tell Stalin about the bomb. Receptive to pressure from Secretary of War Stimson,

Truman recorded his decision to take Japan’s

“old capital” (Kyoto)

off the atomic bomb target list.

Barton Bernstein and Richard Frank, among others, have argued

that Truman’s assertion that the atomic targets were “military objectives”

suggested that either he did not understand the power of the new

weapons or had simply deceived himself about the nature of the targets.

Another statement—“Fini Japs when that [Soviet entry] comes about”—has

also been the subject of controversy over whether it meant that

Truman thought it possible that the war could end without an invasion

of Japan.[30]

Document

39: Diary entries for July 16 through 25, 1945

Source:

Henry Stimson Diary, Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library,

Henry Lewis Stimson Papers (microfilm at Library of Congress)

Stimson did not always have Truman’s ear but historians

have frequently cited his diary when he was at the Potsdam

conference. There Stimson

kept track of S-1 developments, including news of the successful

first test (see entry for July 17) and the ongoing nuclear deployments

for use against Japan. When Truman received a detailed account of the

test, Stimson reported that the “President was tremendously pepped

up by it” and that “it gave him an entirely new feeling of confidence”

(see entry for July 21). Whether

this meant that Truman was getting ready for a confrontation with

Stalin over Eastern Europe and other matters

has also been the subject of debate.

An important question that Stimson discussed with

Marshall, at Truman’s

request, was whether Soviet entry into the war remained necessary

to secure Tokyo’s surrender.

Marshall was

not sure whether that was so although Stimson privately believed

that the atomic bomb would suffice to force surrender (see entry

for July 23). This entry has been cited by all sides of the

controversy over whether Truman was trying to keep the Soviets out

of the war.[31] During a meeting on August 24, Truman agreed

with Stimson that Kyoto,

Japan’s

cultural capital, would not be one of the nuclear targets. For Stimson destroying that city could have

caused such “bitterness” that it might have become impossible “to

reconcile the Japanese to us in that area rather than to the Russians.” Stimson vainly tried to preserve language in

the Potsdam Declaration designed to assure the Japanese about “the

continuance of their dynasty” but received Truman’s assurance that

such a consideration could be conveyed later through diplomatic

channels (see entry for July 24). Hasegawa argues that Truman realized that the

Japanese would refuse a demand for unconditional surrender without

a proviso on a constitutional monarchy and that “he needed Japan’s

refusal to justify the use of the atomic bomb.”[32]

Document

40: "Magic" – Diplomatic Summary, War Department,

Office of Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, No. 1214 – July 22, 1945,

Top Secret Ultra

Source: Record Group 457, Records of the National Security

Agency/Central Security Service, "Magic" Diplomatic Summaries

1942-1945, box

18.

This “Magic” summary includes messages from both

Togo

and Sato. In a long and impassioned

message, the latter argued why Japan

must accept defeat: “it is meaningless to prove one’s devotion [to

the emperor] by wrecking the State.”

Togo

rejected Sato’s advice that Japan

accept unconditional surrender except for one provision: the “preservation

of the Imperial House.” Probably

unable or unwilling to take a soft position in an official cable,

Togo declared that “the whole country … will pit itself against

the enemy in accordance with the Imperial Will as long as the enemy

demands unconditional surrender.”

Documents

41 a-d: Framing the Directive for Nuclear Strikes:

a.

Cable VICTORY 213 from Marshall to Handy, July 22, 1945, Top Secret

b.

Memorandum from Colonel John Stone to General Arnold, "Groves Project," 24 July 1945, Top Secret

c.

Cable WAR 37683 from General Handy to General Marshall, enclosing

directive to General Spaatz, July 24,

1945, Top Secret

d.

Cable VICTORY 261 from Marshall to General Handy, July 25, 1945, 25 July 1945, Top Secret

e.

General Thomas T. Handy to General Carl Spaatz, July 26, 1945, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, Files

no. 5b and 5e (copies from microfilm)

|

| Ground

view of Nagasaki before and after the bombing; 1,000 foot

circles are shown. (Photo from U.S. National Archives, RG

77-MDH) |

Apparently top Army Air Force commanders did not

want to take responsibility for the first use of nuclear weapons

on urban targets and sought formal authorization from Chief of Staff

Marshall who was then in Potsdam.[33] On 22 July Marshall

asked Handy to prepare a draft; General Groves wrote a draft which

went to Potsdam for

Marshall’s approval. Colonel John Stone, an assistant to commanding

General of the Army Air Forces Henry H. “Hap” Arnold,

had just returned from Potsdam

and updated his boss on the plans as they had developed. On 25 July Marshall informed Handy that Secretary

of War Stimson had approved the text; that same day, Handy signed

off on a directive which ordered use of atomic weapons on Japan,

with the first weapon assigned to one of four possible targets—Hiroshima,

Kokura, Niigata, or Nagasaki. “Additional bombs will be delivered

on the [targets] as soon as made ready by the project staff.”

Document

42: Diary Entry, July 24, 1945,

"Japanese Peace Feelers"

Source: Naval Historical Center, Operational Archives,

James Forrestal Diaries

Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal was a regular

recipient of “Magic” intercept reports; this substantial entry reviews

the dramatic Sato-Togo exchanges covered in the 22 July “Magic”

summary (although Forrestal misdated Sato’s cable as “first of July”

instead of the 21st). In contrast to Alperovitz’s argument that Forrestal

tried to modify the terms of unconditional surrender to give the

Japanese an out, Frank sees Forrestal’s account of the Sato-Togo

exchange as additional evidence that senior U.S.

officials understood that Tokyo

was not on the “cusp of surrender.”

[34]

Document

43: Diary entry for July 29, 1945

Source: Joseph E. Davies Papers, Library of Congress,

Manuscripts Division, box

19, 29 July 1945

Having been asked by Truman to join the delegation

to the Potsdam conference,

former Ambassador Davies sat at the table with the Big Three throughout

the discussions. This diary

entry has figured in the argument that Byrnes believed that the

atomic bomb gave the United States

a significant advantage in negotiations with the Soviet

Union. Plainly Davies thought otherwise.[35]

Document

44: "Magic" – Diplomatic Summary, War Department,

Office of Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, No. 1221- July 29, 1945,

Top Secret Ultra

Source: Record Group 457, Records of the National Security

Agency/Central Security Service, "Magic" Diplomatic Summaries

1942-1945, box

18.

The day before the governments of China,

Great Britain,

and the United States

had issued the Potsdam

Declaration demanding the “unconditional surrender

of all Japanese armed forces. “The alternative is prompt and utter

destruction.” In response

to questions from journalists about the government’s reaction to

the ultimatum, apparently Prime Minister Suzuki said that “We can

only ignore [mokusatsu] it. We will do our utmost to complete the war to the bitter

end.” That, Bix argues, represents

a “missed opportunity” to end the war and spare the Japanese from

continued U.S.

aerial attacks.[36] Togo’s

private position was more nuanced than Suzuki’s; he told Sato that

“we are adopting a policy of careful study.”

That Stalin had not signed the declaration (Truman and Churchill

did not ask him to) led to questions about the Soviet attitude. Togo asked Sato to try to meet with Soviet Foreign

Minister Molotov as soon as possible to “sound out the Russian attitude”

on the declaration as well as Japan’s end-the-war initiative. Sato

cabled Togo

earlier that he saw no point in approaching the Soviets on ending

the war until Tokyo

had “concrete proposals.” “Any aid from the Soviets has now become

extremely doubtful.”

Document

45: Memorandum from Major General L. R. Groves to Chief of Staff,

July 30, 1945, Top Secret, Sanitized Copy

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File

no. 5

With more information on the Alamogordo

test available, Groves

provided Marshall with

more detail on the destructive power of atomic weapons. Barton J. Berstein has observed that Groves’s

recommendation that troops could move into the “immediate explosion

area” within a half hour demonstrates the prevalent lack of knowledge

of the dangers of nuclear weapons effects.[37] Groves

also provided the schedule for the delivery of the weapons: the

components of the gun-type bomb to be used on Hiroshima

had arrived on Tinian, while the parts of

the second weapon to be dropped were leaving San Francisco. By the

end of November over ten weapons would be available, presumably

in the event the war had continued.

Document

46: "Magic" – Diplomatic Summary, War Department,

Office of Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, No. 1222 – July 30, 1945,

Top Secret Ultra

Source: Record Group 457, Records of the National Security

Agency/Central Security Service, "Magic" Diplomatic Summaries

1942-1945, box

18.

This report included an intercept of a message

from Sato who reported that it was impossible to see Molotov and

that unless Togo

had a “concrete and definite plan for terminating the war” he saw

no point in attempting to meet with the Soviet Foreign Minister.

Document

47: "Magic" – Diplomatic Summary, War Department,

Office of Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, No. 1225 – August 2, 1945,

Top Secret Ultra

Source: Record Group 457, Records of the National Security

Agency/Central Security Service, "Magic" Diplomatic Summaries

1942-1945, box

18.

An intercepted message from Togo

to Sato showed that Tokyo

remained interested in securing Moscow’s

good office but that it “is difficult to decide on concrete peace

conditions here at home all at once.”

“[W]e are exerting ourselves to collect the views of all

quarters on the matter of concrete terms.”

Barton Bernstein, Richard Frank, and Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, among

others, have argued that the “Magic” intercepts from the end of

July and early August show that the Japanese were far from ready

to surrender. According to Herbert Bix, for months Hirohito

had believed that the “outlook for a negotiated peace could be improved

if Japan

fought and won one last decisive battle,” thus, Hirohito delayed

surrender, continuing to “procrastinate until the bomb was dropped

and the Soviets attacked.”[38]

Document

48: "Magic" – Diplomatic Summary, War Department,

Office of Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, No. 1226 - August 3, 1945,

Top Secret Ultra

Source: Record Group 457, Records of the National Security

Agency/Central Security Service, "Magic" Diplomatic Summaries

1942-1945, box

18.

This summary included intercepts of Japanese diplomatic

reporting on the Soviet buildup in the Far East

as well as a naval intelligence report on Anglo-American discussions

of U.S.

plans for the invasion of Japan. Part II of the summary includes the rest of

Togo’s

2 August cable which instructed Sato to do what he could to arrange

an interview with Molotov.

Document

49: Meeting Notes, August 3, 1945

Source: Clemson University Libraries, Special Collections,

Clemson, SC; Mss 243, Walter J. Brown Papers, box 10, folder 12,

Byrnes, James F.: Potsdam, Minutes, July-August 1945

A number of scholars have used this item in the

papers of Byrne’s aide, Walter Brown, to make a variety of points.

Richard Frank sees this brief discussion of Japan’s

interest in Soviet diplomatic assistance as crucial evidence that

Admiral Leahy had been sharing “MAGIC” information with President

Truman. He also points out that Truman and his colleagues

had no idea what was behind Japanese peace moves, only that Suzuki

had declared that he would “ignore” the Potsdam Declaration. Alperovitz, however, treats it as additional

evidence that “strongly suggests” that Truman saw alternatives to

using the bomb.[39]

Documents

50a-c: Weather delays

Document

50a: CG 313th Bomb Wing, Tinian cable APCOM 5112 to War Department, August 3,

1945, Top Secret

Document

50b: CG 313th Bomb Wing, Tinian cable APCOM 5130 to War Department, August 4,

1945, Top

Secret

Document

50c: CG 313th Bomb Wing, Tinian cable APCOM 5155 to War Department, August 4,

1945, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, Tinian

Files, April-December 1945, box

21 (copies courtesy

of Barton Bernstein)

The Hiroshima

“operation” was originally slated to begin in early August depending

on local conditions. As these

cables indicate, reports of unfavorable weather delayed the plan.

The second cable on 4 August shows that the schedule advanced to

late in the evening of 5 August. The transcriptions on the documents appear on

the archival originals.

Document

51: "Magic" – Far East Summary, War Department, Office

of Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, no. 502, 4 August 1945

Source: RG 457, Summaries of Intercepted Japanese Messages

("Magic" Far East

Summary, March 20, 1942

– October 2, 1945),

box

7, SRS 491-547

This “Far East Summary” included reports on the

Japanese army’s plans to disperse fuel stocks to reduce vulnerability

to bombing attacks, the text of a directive by the commander of

naval forces on “Operation Homeland,” the preparations and planning

to repel a U.S. invasion of Honshu, and the specific identification

of army divisions located in, or moving into, Kyushu. Both

Richard Frank and Barton Bernstein have used intelligence reporting

and analysis of the major buildup of Japanese forces on southern

Kyushu to argue that U.S.

military planners were so concerned about that development that

by early August 1945 they were reconsidering their invasion plans.[40]

Document

52: "Magic"

– Diplomatic Summary, War Department, Office of Assistant Chief

of Staff, G-2, No. 1228 – August 5, 1945, Top Secret Ultra

Source: Record Group 457, Records of the National Security

Agency/Central Security Service, "Magic" Diplomatic Summaries

1942-1945, box

18.

This summary included several intercepted messages

from Sato, who conveyed his despair and exasperation over what he

saw as Tokyo’s inability to develop terms for ending the war: “[I]f

the Government and the Military dilly-dally in bringing this resolution

to fruition, then all Japan will be reduced to ashes.”

Sato remained skeptical that the Soviets would have any interest

in discussions with Tokyo:

“it is absolutely unthinkable that Russia

would ignore the Three Power Proclamation and then engage in conversations

with our special envoy.”

VI.

The First Nuclear Strikes

Document

53: Memorandum from General L. R. Groves to the Chief of Staff,

August 6, 1945, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File

no. 5b (copy from microfilm)

|

| Hiroshima,

after the first atomic bomb explosion. This view was taken

from the Red Cross Hospital Building about one mile from the

bomb burst. (Photo from U.S. National Archives, Still Pictures

Branch, Subject Files, "Atomic Bomb") |

The day after the bombing of Hiroshima, Groves

provided Chief of Staff Marshall with a report which included messages

from Captain William S. Parsons and others about the impact of the

detonation which immediately killed at least 70,000, with many dying

later from radiation sickness and other causes. [41]

How influential the atomic bombings of Hiroshima

and later Nagasaki compared to the impact of the Soviet declaration

of war were on the Japanese decision to surrender has been the subject

of controversy among historians. Sadao Asada emphasizes the shock

of the atomic bombs, while Herbert Bix has suggested that Hiroshima

and the Soviet declaration of war made Hirohito and his court believe

that failure to end the war could lead to the destruction of the

imperial house. Frank and Hasegawa divide over the impact of the

Soviet declaration of war, with Frank declaring that the Soviet

intervention was "significant but not decisive" and Hasegawa

arguing that the two atomic bombs "were not sufficient to change

the direction of Japanese diplomacy. The Soviet invasion was."

[42]

Document

54: Memorandum of Conversation, "Atomic Bomb," August 7, 1945

Source: Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Papers

of W. Averell Harriman, box

181, Chron File

Aug

5-9, 1945.

The Soviets already knew about the U.S.

atomic project from espionage sources in the United

States and Britain

so Molotov’s comment to Ambassador Harriman about the secrecy surrounding

the U.S.

atomic project can be taken with a grain of salt, although the Soviets

may have been unaware of specific plans for nuclear use.

Documents

55a and 55b: Early High-level Reactions to the Hiroshima Bombing

Document

55a: Cabinet Meeting and Togo's Meeting with the Emperor, August

7-8, 1945

Source: Gaimusho (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) ed. Shusen Shiroku

(The Historical Records of the End of the War), annotated by Jun

Eto, volume 4, 57-60 [Excerpts] [Translation by Toshihiro Higuchi]

Document

55b: Diary Entry for Wednesday, August 8 , 1945

Source: Takashi

Itoh, ed., Sokichi Takagi:

Nikki to Joho [Sokichi Takagi: Diary and Documents] (Tokyo,

Japan:

Misuzu-Shobo, 2000), 923-924 [Translation by Hikaru Tajima]

|

| Ground

Zero at Hiroshima Today: This was the site of Shima Hospital;

the atomic explosion occurred 1,870 feet above it (Photo

courtesy of Lynn Eden, www.wholeworldonfire.com) |

|

Excerpts from the Foreign

Ministry's compilation about the end of the war show how news of

the bombing reached Tokyo as well as how Foreign Minister's Togo

initially reacted to reports about Hiroshima. When he learned of

the atomic bombing from the Domei News Agency, Togo believed that

it was time to give up and advised the cabinet that the atomic attack

provided the occasion for Japan to surrender on the basis of the

Potsdam Declaration. Togo could not persuade the cabinet, however,

and the Army wanted to delay any decisions until it had learned

what had happened to Hiroshima. When the Foreign Minister met with

the Emperor, Hirohito agreed with him; he declared that the top

priority was an early end to the war, although it would be acceptable

to seek better surrender terms--probably U.S. acceptance of a figure-head

emperor--if it did not interfere with that goal. In light of those

instructions, Togo and Prime Minister Suzuki agreed that the Supreme

War Council should meet the next day. [42a]

An entry from Admiral

Tagaki's diary for August 8 conveys more information on the mood

in elite Japanese circles after Hiroshima, but before the Soviet

declaration of war and the bombing of Nagasaki. Seeing the bombing

of Hiroshima as a sign of a worsening situation at home, Tagaki

worried about further deterioration. Nevertheless, his diary suggests

that military hard-liners were very much in charge and that Prime

Minister Suzuki was talking tough against surrender, by evoking

last ditch moments in Japanese history and warning of the danger

that subordinate commanders might not obey surrender orders. The

last remark aggravated Navy Minister Yonai who saw it as irresponsible.

That the Soviets had made no responses to Sato's request for a meeting

was understood as a bad sign; Yonai realized that the government

had to prepare for the possibility that Moscow might not help. One

of the visitors mentioned at the beginning of the entry was Iwao

Yamazaki who became Minister of the Interior in the next cabinet.

Document

56: Navy Secretary James Forrestal to President Truman, August 8, 1945

Source: Naval Historical Center, Operational Archives,

James Forrestal Diaries

General Douglas MacArthur had been slated as commander

for military operations against Japan’s

mainland, but this letter to Truman from Forrestal shows that the

latter believed that the matter was not so settled. Richard Frank

sees this as evidence of the uncertainty felt by senior officials

about the situation in early August; Forrestal would not have been so “audacious”

to take an action that could ignite a “political firestorm” if he

“seriously thought the end of the war was near.”[43]

Document

57: Memorandum of Conversation, "Far Eastern War and General

Situation," August 8, 1945,

Top Secret

Source: Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Papers

of W. Averell Harriman, box

181, Chron File

Aug

5-9, 1945

Shortly after the Soviets declared war on Japan,

in line with commitments made at the Yalta

and Potsdam conferences,

Ambassador Harriman met with Stalin, with George Kennan keeping

the U.S.

record of the meeting. After Stalin reviewed in considerable detail

Soviet military gains in the Far East, they

discussed the possible impact of the atomic bombing on Japan’s

position (Nagasaki had

not yet been attacked) and the dangers and difficulty of an atomic

weapons program. According to Hasegawa, this was an important,

even “startling,” conversation: it showed that Stalin “took the

atomic bomb seriously”; moreover, he disclosed that the Soviets

were working on their own atomic program.[44]

Document

58: Memorandum of Conference with the President, August 8, 1945 at 10:45 AM

Source:

Henry Stimson Diary, Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library,

Henry Lewis Stimson Papers (microfilm at Library of Congress)

At their first meeting after the dropping of the

bomb on Hiroshima, Stimson

briefed Truman on the scale of the destruction, with Truman recognizing

the “terrible responsibility” that was on his shoulder. Consistent with his earlier attempts, Stimson

encouraged Truman to find ways to expedite Japan’s

surrender by using “kindness and tact” and not treating them in

the same way as the Germans. They

also discussed postwar legislation on the atom and the pending Henry

D. Smyth report on the scientific work underlying the Manhattan

Project and postwar domestic control of the atom.

Documents

59 a-c: The Attack on

Nagasaki:

a.

Cable APCOM 5445 from General Farrell to O’Leary [Groves

assistant], August 9, 1945,

Top Secret

b.

COMGENAAF 8 cable CMDW 576 to COMGENUSASTAF, for General Farrell,

August 9, 1945, Top secret

c.

COMGENAAF 20 Guam cable AIMCCR 5532 to COMGENUSASTAF Guam,

August 10, 1945, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, Tinian

Files, April-December 1945, box

20, Envelope

G Tinian

Files, Top Secret

|

| The

mushroom cloud over Nagasaki shortly after the bombing on

August 9. (Photo from U.S. National Archives, RG 77-AEC) |

The prime target for the second atomic attack was

Kokura, which had a large army arsenal and ordnance works, but various

problems ruled that city out; instead, the crew of the B-29 that

carried "Fat Man" flew to an alternate target at Nagasaki.

These cables are the earliest reports of the mission; the bombing

of Nagasaki killed immediately at least 39,000 people with more

dying later. According to Frank, the "actual total of deaths

due to the atomic bombs will never be known," but the "huge

number" ranges somewhere between 100,000 and 200,000 people.

Barton J. Bernstein and Martin Sherwin have argued that if top Washington

policymakers had kept tight control of the delivery of the bomb

instead of delegating it to Groves the attack on Nagasaki could

have been avoided. The combination of the first bomb and the Soviet

declaration of war would have been enough to induce Tokyo's surrender.

By contrast, Maddox argues that Nagasaki was necessary so that Japanese

"hardliners" could not "minimize the first explosion"

or otherwise explain it away.[45]

Document

60: Ramsey Letter from Tinian Island

a.

Letter from Norman Ramsey to J. Robert Oppenheimer,

undated [mid-August 1945], Secret, excerpts

Source: Library of Congress, J. Robert Oppenheimer Papers,

box

60, Ramsey,

Norman

b.

Transcript of the letter prepared by editor.

Ramsey, a physicist, served as deputy director

of the bomb delivery group, Project Alberta.

This personal account, written on Tinian,

reports his fears about the danger of a nuclear accident, the confusion

surrounding the Nagasaki

attack, and early Air Force thinking about a nuclear strike force.

VII.

Toward Surrender

Document

61: "Magic" – Far East Summary, War Department, Office

of Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, no. 507, August 9, 1945

Source: RG 457, Summaries of Intercepted Japanese Messages

("Magic" Far East

Summary, March 20, 1942

– October 2, 1945),

box

7, SRS 491-547

Within days after the bombing of

Hiroshima,

U.S. military

intelligence intercepted Japanese reports on the destruction of

the city. According to an “Eyewitness Account (and Estimates

Heard) … In Regard to the Bombing of Hiroshima”: “Casualties have